JOSEPH GAGE (1689-1768)

By Martin Murphy

Joseph Gage became a legend in his own lifetime, largely due to Alexander Pope’s satirical portrait of him as an example of venality and folie de grandeur. In fact the truth is more remarkable than the legend.

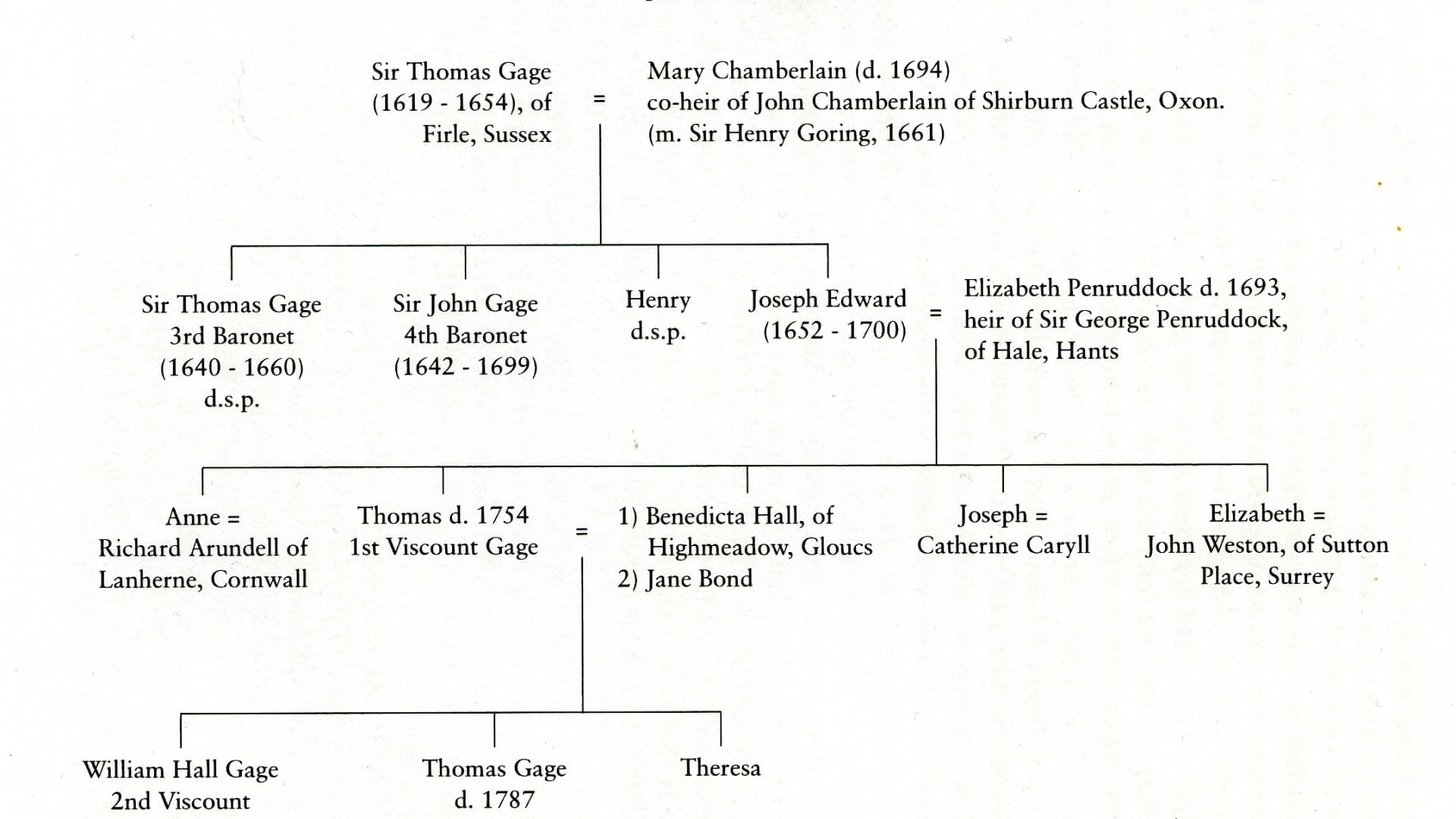

In 1694 Joseph’s father, Joseph Edward Gage, inherited Shirburn Castle, Oxfordshire, on the death of his mother, the last survivor of the Chamberlain family who had lived at Shirburn since the 15th century. Both Chamberlains and Gages were Catholics, and so Joseph Edward sent his two sons, Thomas and Joseph, to be educated in France at the Jesuit college of La Flèche. There they went under the disguise of Thomas and Isaac Donne, since Wlliam III had recently revived the law penalising Catholics who sent their children abroad ‘to be educated in popery’.

Little is known about Joseph in the years that followed immdiately after he left La Flèche in 1702. His elder brother Thomas inherited Shirburn in 1700, but sixteen years later sold it to the Earl of Macclesfield for £25,696. In his first will of 13 July 1714 Joseph left his brother the manors of Pett and Mersham . As a younger brother, a Jacobite, and a Catholic, he had limited career options. Others in his position would have chosen service in a foreign army, but he first made his name as a professional gambler in Paris, then entering a new era of permissiveness under Louis XIV’s easy-going successor, the Regent Duke of Orléans. In 1719 Joseph was released from prison at the behest of the Dowager Duchess of Orléans, one of his gaming partners. He was keeping exalted company. That same year he became associated with John Law, the Scottish financial wizard whose ‘System’, based on the supply of paper money, was adopted by the Regent as a means of stimulating the economy and reducing the national debt. Gradually Law extended his control over the entire economy. Like Gage he was a gambler, but on a far larger scale. Since his bank’s limited reserves were insufficient to bear the weight of his System he formed a Mississippi Company to exploit the virgin territories of French Louisiana, said to contain fabulous deposits of precious metal. In November 1718 he formed a syndicate with Gage and the Irish banker Richard Cantillon to purchase one of the parcels of land in Louisiana which were put on the market for development. Paris went wild with Mississippi mania, and ‘Beau Gage’, or ‘Le Sieur Guesch’ as he was known, was one of the Mississippi millionaires, with an elegant residence in the Faubourg St Germain and a princely equipage and liveried servants to go with it. Towards the end of 1719 an English diplomat in Paris described him as a Croesus. ‘He reckons himself already worth 50 thousand a year, and will not be satisfied till he has 100 thousand. I wish a good share of these riches would be showered down some Thursday night in Downing Street’. In October 1719 the English ambassador forwarded letters from him to the Lord Chancellor and Prime Minister, offering to transfer his gains to London in return for a peerage and exemption from the law which debarred Catholics from purchasing estates.

But cracks were beginning to appear in the System. The Mississippi scheme fell victim to its own inflated publicity, and the public proved reluctant to be bullied out of its preference for specie, rather than paper. Gage was now working in tandem with one of the most reckless of the speculators, Lady Mary Herbert, the eldest daughter of the Marquess (Jacobite Duke) of Powis. Their partnership was to last all their lifetimes, though Lady Mary successfully evaded Joseph’s proposals of marriage. She had set her sights higher up the social scale, though she was destined to remain single to the end. Both Joseph and Mary continued to believe in the infallibility of Law’s System when others, more careful, got out of paper into specie despite the measures that Law took to prevent a run on the bank. When the whole System collapsed on 22 May 1720, a Black Tuesday, both Joseph and Mary were left holding valueless shares and banknotes. The Herbert family, with massive debts of over £170,000, faced ruin. The ‘congenial souls’, as Pope called them, blamed their predicament on the Irish banker Richard Cantillon, whom they sued for fraud and usury. Their lawsuit against him and his heirs dragged on for years.

To avoid their creditors Joseph and Mary moved from place to place, often in disguise. Then Mary had one of her many brainwaves. The Herberts’ lead mines in Montgomeryshire had made a European reputation, and on the strength of this reputation she obtained from the King of Spain a licence to re-open the disused silver mine at Guadalcanal, in the Sierra Morena. Joseph was essential to the scheme as its administrator. The problems of recruiting qualified personnel, getting them to the Andalusian outback, draining the mine and smelting the ore were enormous, but Joseph was a quick learner. The Guadalcanal mine was successfully drained, and sample ore extracted, only for the pair’s Spanish partners to renege on the contract. Joseph was tireless in prospecting other mines in the area and beyond, and one of them, at Cazalla de la Sierra, turned out to make a profit which made it possible for him to retire to Paris.

He was now in a strong position to demand from Mary Herbert the reward he deserved for his loyalty and industry in her service. It required all her considerable powers of guile and duplicity to avoid what he wanted – her hand in marriage. Instead she found an alternative and well-dowered bride for him in the shape of Catherine Caryll, another expatriate Jacobite resident in Paris. The wedding took place in Paris two days before Christmas 1747, but it was short-lived. The bride died three months later, leaving her husband a widower. It is significant that the person given power of attorney over the estate of the deceased was Lady Mary Herbert, acting on behalf of ‘the Hon. J.E. Gage, commonly called Count Gage’.

Joseph lived on for another twenty years at an address in the rue des Petits Augustins on the Left Bank. He and his brother Thomas were never reconciled, and in his will of 3 September 1753 he left Thomas and to each of his two sons ‘one shilling of lawful currency’. As late as 1754 he was still pursuing his lawsuit against Richard Cantillon’s heirs (Cantillon himself having died earlier in suspicious circumstances). An Englishman who fell into conversation with him in a Parisian tavern in June 1763 found him to be a cheerful old gentleman who ‘spoke much of the folly of avarice and ambition, which he said had no end’. He died five years later.

This article is based on a book written by Martin Murphy: The Duchess of Rio Tinto: The Story of Mary Herbert and Joseph Gage. By Martin Murphy. Oxford: St Clements Press, 2015. Pp. viii + 136. ISBN 978-0993394409. You can buy a copy of this book by clicking HERE