GENERAL THOMAS GAGE

William Shirley, by capturing Louisburg, began the conquest of Canada: it was finished by Wolfe and Amherst, with Thomas Gage serving under the latter. Shirley was Governor of Massachusetts from 1741 to 1749, and again from 1753 to 1756; it was Gage’s duty, in a similar office, to try to carry out the insensate policy of the British government, from May 1774, to October 1775, when he left Boston, jeered at and execrated, the last Governor of the Imperial connection. Thus these two men whose homes in Sussex, England were but twelve miles apart, were prominently connected with some of the most stirring events in the histories of the United States and Canada. Was it also more than a coincidence that Thomas Paine first expounded his “revolutionary theories” in the White Hart, Lewes – again just a few miles from the Gage ancestral home at Firle Place?

Thomas Gage came from an established Sussex family, who had lived at Firle in East Sussex since the fifteenth century. The family remained staunchly Catholic (to their cost) until in the mid-1720s, Sir William Gage, the seventh baronet, decided to convert to the Protestant Church of England. According to Alexander Pope, who knew him well, he did so not from high principle but because he wished to ‘have the use of horses, forbidden to all those who refused to take the oath of allegiance to the Church’. Thus, the Gage’s returned to public service, flourished, and were created viscounts. Thomas’s father (another Thomas), was raised to the peerage as the first Viscount Gage in 1720. The first Viscount and his wife Benedicta Hall were the parents of our General Thomas Gage, he was their second son born in 1719/1720. Benedicta was heiress of Highmeadow, in Gloucestershire, where they lived until Thomas inherited Firle Place from his cousin, William Gage, upon his death in 1744. Around the age of nine, Gage was sent to Westminster School in London, and studied there for eight years. The school had a positive effect on Thomas, and he grew up to be disciplined and hardworking, ambitious, prudent and serious, upright and well-meaning. As a second son – he would not inherit – leaving two choices of occupation open to him: the church or the army. Thomas elected to pursue an army career and a King’s commission was purchased for him on January 30, 1741 as a Lieutenant in Colonel Cholmondeley’s Regiment of Foot, where he commenced service in Ireland. Thomas Gage found army life pleasing. He enjoyed its pageantry, and took comfort in its discipline. He became a seasoned soldier, witnessing some of the most gruesome battles of the time. He was present at the British defeat at Fontenoy on May 11, 1745, one of the bloodiest conflicts of the eighteenth century, ending with 30,000 fallen men on a Flanders field, amidst scenes of horror and brutality beyond description. [1]

A year later, in Scotland, Thomas was present for another epic slaughter. On this occasion his was the winning side at the battle of Culloden on April 27, 1746 where the Highland clans were defeated and Drumossie Moor was left carpeted with corpses. [2]

After Culloden, Gage returned to Flanders. Here he engaged in a period of peacetime soldiering, on the staff of the Earl of Albemarle, father of an old school friend. In 1755, he was posted to America with General Edward Braddock. Gage commanded the vanguard on Braddock’s expedition against the French in the Ohio Valley. On July 9, 1755, the force blindly marched into a forest ambush at Fort Duquesne, was nearly annihilated, and Braddock was killed. True to form, Gage conducted himself with courage in combat. Wounded himself, he improvised a rear guard that allowed the escape of George Washington.[3]

Gage stood out for honourable behaviour, zeal and integrity during the course of the French and Indian War that followed. It was through this time that a friendship developed between Gage and the young Virginian and fellow-officer, George Washington. They came to hold one another in respect for bravery in the face of adversity – thus was the ironic twist of fate years later, these two men would find themselves leading opposing sides.

In order to secure a permanent colonelcy for himself, and because of the peculiar conditions of warfare in the woods, Thomas Gage raised a new type of regiment in 1757, called the “80th Foot”, or “Gage’s Light Armed Infantry”. This regiment came to be designated as a landmark in military history, for he had organized ‘the first definitely light-armed regiment in the British army.’ [4] dressed in brown camouflage coats with black buttons. Gage departed for Brunswick (now New Brunswick in New Jersey), where he set up a recruiting headquarters. Thomas did not go there just for military purposes alone. Indeed, it appears his main objective was to spend the Christmas holidays with the Peter Kemble family. Thomas was much taken by Peter’s daughter Margaret, then about twenty-four years of age, and whose proud beauty was well-known in social circles through the middle colonies.

In July 1757 Thomas was ordered to lead the Light Infantry against the ramparts of Fort Ticonderoga, in a headlong frontal assault on a strongly fortified position. With enormous courage, Gage and his men charged directly into an impenetrable abattis of fallen timber, cunningly cut and disguised to trap them. As Gage’s Light Infantry struggled with heroic stoicism to break through the trap, they were caught in a deadly crossfire. Bodies were left in grotesque and tangled postures, suspended from the branches, on that killing ground. More than 1600 men fell, and once again Gage was among the many wounded.[5]

The reason for recounting these horrific incidents is the fact that they certainly would have influenced Thomas Gage’s decisions and attitudes during his ensuing career. Gage’s courtship of the “Duchess”, as his fellow-officers called Margaret proved successful. They were married on December 8, 1758 on the veranda of Mt. Kemble, in Morristown. The Gage’s honeymoon was spend only in part in New Jersey, for the new year brought with it orders to assume the important command of Albany, and all the forts in the neighbourhood. General Sir Jeffrey Amherst, the Commander in Chief of the British forces in North America, was well disposed towards the new brigadier, and hoped to make good use of his talents. Accordingly, the newly married couple proceeded to New York, and thereafter to Albany until the spring. The happy couple did not lack for good food; Gage had arranged for hams, tongues and lemons to be sent up from New York. Gage also made every effort to make his officers men as comfortable as possible in their winter quarters.

William Pitt, the English Prime Minister, pressed the impetus to shatter French Canada. General James Wolfe was given instructions to assail Quebec. Simultaneously Amherst was to move northward towards Montreal via Lake Champlain, and a third force was to take Niagara and La Galette and to proceed to the same destination via the St. Lawrence under Brigadier General John Prideaux. In May 1759 Amherst marched northward from Albany, followed by Prideaux who had laid siege to Niagara and reoccupied Oswego early in July. However, Prideaux was accidentally killed shortly thereafter, and Amherst promptly ordered Gage to execute Prideaux’s instructions to attack La Galette and proceed to Montreal. For a variety of reasons, Gage decided not to proceed to La Galette.

The failure of Amherst, partly because of Gage, to press on to Montreal made the task laid out for Wolfe more hazardous. However, Wolfe was willing to risk everything for success, he pushed forward in the face of almost overwhelming odds, ascending the cliffs to the Plains of Abraham to route the Marquis de Montcalm. Dead together with his antagonist, Wolfe was acclaimed the conqueror of Canada. In fact, Canada was not completely conquered.

Once more in Albany for the winter season, Gage was joined by his wife, she had spent the summer at Brunswick. In the late spring of 1760, Amherst took to the field, Gage accompanied him. The Marquis de Vaudreuil, the Governor of Canada, Montcalm’s successor, had raised a large force in Montreal during the winter and laid siege to Quebec in April. General James Murray advanced up the St. Lawrence; Brigadier General William Haviland, under orders from Amherst led forward a body of ten thousand men from Oswego, Gage commanded the rear of the army. Amherst put together a great armada of small ships and boats at Oswego, sailed across Lake Ontario and down the St. Lawrence to La Galette and reached Montreal on September 6, 1760. Two days later Vaudreuil surrendered.[6]

From a historical standpoint, today we have the advantage of hindsight. When the British won the Seven Years War, which brought subsequently unprecedented wealth for the country, particularly in the instance of India, the dye was also cast concerning the future of the American colonies. Once the French menace was no longer a threat in Canada, there was no need for the protection or support of the British army or navy. This subtle shift of balance made the independence of the Americans inevitable – no matter who had been Commander and Chief of the British forces at the outbreak of the American revolutionary war. It also encouraged the colonists to feel they owed little now to the Government in England. Furthermore the American habit to think in terms of rights within the continent, rather than an implicit duty towards an Empire, became ever more paramount.[7]This fundamental difference in attitude was the result of one very significant factor: in England under the system of primogeniture, estates passed to the first-born. However, in the event second and subsequent sons emigrated to America, there they had the opportunity to become landowners. It is this issue that was the crux of the rubric for rebellion. Interestingly though, in a new publication, The Quartet, by Joseph P. Ellis, he points out that in 1776 the thirteen American colonies declared themselves independent states, that came together temporarily to win their rights, then they would go their separate ways. The government they created in 1781, called the Articles of Confederation, was not really much of a government at all and was never intended to be. The resolution declaring independence, approved on July 2, 1776, clearly stated that the former colonies were leaving the British Empire not as a single collective but rather as “Free and Independent States”. There was no sense or desire to come together as a new nation or one country: this occurred later by the way of the orchestration of the second American Revolution of 1783-1789, which is the topic of Ellis’s book.[8]

The Articles of Surrender were signed by Vaudreville and Amhurst on September 8, 1760, and the French troops returned to their mother country. Amherst was at liberty to organize Canada as he would, and he quickly arranged for three military governments. James Murray continued in command at Quebec, Gage was made Governor of Montreal, and Ralph Burton was assigned to the Three Rivers region.

Thomas Gage proved himself a competent administrator: tact and wisdom were the hallmarks of his three year tenure, where he assumed control of civil as well as military functions. The new Governor’s lawmaking duties were tedious, reduced to mundane details such as establishing regulations as to the proper disposal of personal waste or keeping streets swept of snow. Montreal was a real backwater to an officer determined to achieve success in his profession. While ambitious, Gage, proved to be very popular with the citizens of Montreal. Gage was a wise and tolerant governor, respected for his strong sense of justice and fair play, his caution and good humour won him public acclaim. He forbade forestalling by merchants, establishing standard measures, setting the price of firewood and bread, and preventing merchants from selling liquor to soldiers or to Indians, rates for cartage, regulated currency and he forbade monopolies of any sort, that always accompanied French rule.[9] He was also accommodating with the Catholic bishops, although in private he regarded them as vicious bigots. Gage was merciful to the Indians, despite the fact he had seen settlers with their scalps off, and was bitterly aware of their treacheries. In a letter to Amherst, he commented ‘Indians apply for provisions. They are a cursed crew, but He can’t see them perish with hunger’.

In all these matters, Gage was given a practically free hand. Had the same powers been vested in him in Boston as Governor of Massachusetts, the situation may have been very different. There he was in the deplorable position of attempting to carry out, without sufficient forces, policies he knew to be ridiculous.

The dull life and tedium of the long winters in Montreal were no doubt enlivened for Gage by the companionship of his wife who came to Montreal immediately after the conquest and remained until the ice broke up in the lakes in the spring of 1763. They lived in the Chateau de Remezay and suffered from colds. Their first son, Henry, was born on March 4, 1761. A year later a daughter, Maria Theresa was born, and when Margaret Gage left for New York early in 1763 she was again pregnant, and in the spring a third child, christened William, was born.

Thomas Gage was elevated a Major General in 1761, and he became increasingly disillusioned in Montreal, writing disconsolately to Amherst on May 9, 1763[10] ‘…. I can [not] say I am in general tired of America, but very much of this cursed climate and I must be bribed very high to stay here any longer.’ Amherst proposed to obtain a leave of absence and that Gage, as the senior officer in America, might succeed to the supreme command in New York, at least temporarily. Gage readily agreed. In the spring of 1763 news came to Canada of the definitive peace – The Treaty of Paris – that gave Canada to Britain. New France was absorbed into British North America from Arcadia to the Mississippi Valley.

Amhurst duly returned to England in October 1763. Gage left Montreal in a hurry to avoid spending another winter there, by way of Crown Point and Albany to New York where he arrived on the night of Wednesday, November 16th. The next morning he took over as commander in chief. He would hold the post for the next twelve fateful years. In September 1764 Amhurst declared that he had no wish to return to America. Thomas Gage’s position became permanent: he was formally commissioned by the King on November 16, 1764.

By June 1764 the Gages had moved in to a double house on Broad Street surrounded by elegant gardens. Historians have commented disparagingly that the address was not especially exclusive. Their neighbours comprised a wigmaker and hairdresser opposite, and next to the tonsorial artists was the residence of Bernard Andrews, an “embroiderer”. I have come to discover, that it is important to walk through history, which often provides insight or a better understanding of circumstances. One day I explored Broad Street, to find that City Hall (now Federal Hall National Memorial) was at the end of the block. This possibly explains why the Gages may have chosen this location, General Gage was able to walk to work!

For the next nine years the house became the centre of all British military activities in America, were probably the happiest in the life of Thomas Gage. Professionally, he had risen almost to the top of the ladder. There must have also been satisfaction in the fact he administered the peace-time standing army in its far flung forts across half a continent. In addition the Gages were famous throughout the colonies for “conjugal felicity”. They were enormously popular in New York social circles, and led society in style, fashion and the making of a new world. They lived in close proximity to Trinity Church, where they enjoyed a comfortable pew. They entertained liberally; they met with all the distinguished visitors in the town including such persons as Lord William Campbell, Sir William Draper, the great Cherokee chiefs Attakullakulla and Ouconnostotah, James Otis and George Washington (though by this time, their relationship had begun to cool) and cut good figures at tea parties, in the theatre and at the horse races. Thomas was modest, diffident, good-natured, and generous, the new commander was far more attractive and approachable than the haughty, imperious and taciturn Amherst. He subscribed for copies of James Adair’s famous History of the American Indians, encouraged Thomas Hutchins and others to make maps of the American interior, and provided a pass to certain distinguished mathematicians to aid them in reaching Lake Superior to observe the transit of Venus. Thomas believed in education, and his many children were sent “home” to school as soon as they were old enough to endure the voyage, where they were looked after by Thomas’s brother, William Hall, the second Viscount and his wife, “Aunt Betsy”, living at Firle Place.

Margaret was one quarter English, one quarter Greek, one quarter Dutch and one quarter French, and was known throughout the colonies for her unusual beauty. Sensitive and exquisite, she had charm rather than statuesque looks, with large dark eyes. Margaret’s father was the Honourable Peter Kemble, one of the wealthiest and most prominent men in the colony of New Jersey, a staunch Tory, and who at the time was the presiding officer of the Royal Council of New Jersey. Peter Kemble was by far the largest landowner in Morris County. His forbears had traded in Turkey and Smyrna, Peter was born at Smyrna in 1704, his mother was a native of Scio, came to New York around 1730 and his first marriage was to Gertrude Bayard, through whom Margaret was the first cousin of Pierre van Cortland, first Lieutenant-Governor of the State of New York; she was also connected to General Philip Schuyler of the Revolutionary Army; James de Lancey, Chief Justice and Lieutenant-Governor of the Province of New York; General Oliver de Lancey, senior loyalist Brigadier General of New York in the Revolutionary war; John van Cortland, the prominent New York City Whig leader in 1776, among others – a striking illustration of the close, as well as wide, kinship of the chief colonial families of New York, that politically and socially proved such a force in the colony.[11]

Peter Kemble settled at New Brunswick, New Jersey, where he entered into a successful business. Afterwards he purchased land near Morristown, where he built a timber frame house, “Mount Kemble” in 1755, and lived here until his death on February 23rd, 1789, at the great age of 85. The estate stood as a proud outpost of the mercantile-landowning community of New Jersey. Well read in the Classics, he was known to possess a fine library, and owned a number of slaves.

On a visit to Boston, Thomas Gage commissioned John Singleton Copley to paint his portrait in 1768-9 (you can read more about this portrait in a separate article here). While it is a largely formulaic composition, Gage was valuable patron for Copley. This portrait hanging in the Gage’s home in Broad Street in New York advertised the artist’s talents. Indeed Captain John Small of Gage’s staff wrote to Copley in 1769, that the canvas was ‘universally acknowledg’d to be a very masterly performance, elegantly finish’d and a most striking Likeness; in short it has every property that Genius, Judgement and attention can bestow on it.’ In 1771 Thomas shipped this portrait back to England, for inclusion in the Royal Academy exhibition, which helped establish Copley’s reputation. ‘….The Generals Picture was receiv’d at home with universal applause and Looked on by real good Judges as a Masterly performance. It is placed in one of the Capital Apartments of Lord Gage’s House in Arlington Street; and as a test of its merit it hangs between Two of Lord and Lady Gages, done by the celebrated Reynolds, at present Reckon’d the Painter laureate of England’[12] It was his elder brother, the second Viscount, who purchased Thomas’s commissions as he rose through the ranks, and constantly pressed for the advancement in his career.

The Gages subsequently commissioned a companion portrait of Margaret. At first, Copley was reluctant to come to New York, he was occupied building a house in Boston. However, he was persuaded to come on the promise that in addition to Margaret, numerous commissions would be secured, organized by Stephen Kemble. In April 1771 Stephen send a short list of subscribers to Copley: at the top of the list was a commission for two 40 x 50 inch portraits of his sister, Margaret. Copley commenced Margaret’s portrait on June 17, 1771, within three days of his arrival in New York. The artist felt that his success in New York depended upon this portrait and indeed, in the instance of the Timken Museum canvas, this is quite unlike anything he had painted in Boston. The artist proudly wrote to Henry Pelham on November 6, 1771 ‘I have done some of my best portraits here, particularly Mrs. Gage’s, which has gone to Exhibition. It is I think beyond Compare the best Lady’s portrait I ever Drew; but Mr. Pratt says of it, It will be flesh and Blood these 200 years to come, that every Part and line in it is Butifull (sic.), and that I must get my Ideas from Heaven.’Copley’s treatment of chiaroscuro is indeed a notable feature in this portrait, which is quite unparalleled in terms of his New England period in its sophistication. While he has clearly drawn upon the “Cumaean Sibyl” as the source of inspiration for this pose, surely a reference was also intended to Margaret’s Smyrnan/Greek antecedents?

Despite the enthusiasm with which this canvas of Mrs. Gage was greeted, it later faded into obscurity. For many years it hung in a back corridor at Firle Place, considered to be of Charlotte Ogle, Mrs. Gage’s daughter, painted by Nathanial Dance until Barbara Parker’s pioneering study in 1938. What happened to the second portrait of Mrs. Gage? Could there be any link with the Copley portrait, now in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum? Likewise, it was mis-attributed and for a while referred to as a portrait of Mrs. Thrale, and also called Nathanial Dance. They are the same canvas size, the second holds a letter dated 1771, they sit on similar sofas (while the material covering is of different colours), and they do share some similarities in terms of physiognomy. If the artist had been commissioned to paint two portraits of his sitter, and the first had been a formal pose, what might have been his choice for the second? Could he have intended to show Margaret, relaxed and ‘at home’, her hair is neither dressed nor powdered, she wears no make-up, and she is simply wearing her house-robe: in other words this was intended as a study of informality? Some experts find the exotic beauty depicted in the Timken portrait hard to equate to the plain figure in the Los Angeles canvas. Could Copley have over-embellished his formal portrait, given the fact it is clear he wished to establish his reputation with it? We know from contemporary descriptions of Margaret she was not a great beauty in the accepted sense, however, that her looks were distinctive and unusual. It is worth noting that Benjamin West wrote to Copley on January 6, 1773 ‘…the portrait of Mrs. Gage has received every praise from the lovers of arts, her Friends did not think the likeness so favourable as they could wish, but Honour’d it as a piece of art. Sir Joshua Reynolds and other artists of distinguished merit have the Highest esteem for you and your works.’

Thomas Gage’s finances steadily increased during his American service. As Commander in Chief he received a salary of £10 a day, no mean sum then. Further, he was given one hundred rations per day, which he did not draw, but for which the army paid him £2 10s. cash, together with approximately £164 for heating (“firing”). He was also paid the salary of a Colonel, since in theory he retained the command of one regiment or another from 1757, until his death. As Colonel, he enjoyed further perquisites. From the 1760s onwards he was concerned for the future of his family – 11 children in total – and he purchased large amounts of land with the prospect that their value would increase as the colonies developed. In 1765 though the assistance of Governor Montague Wilmot of Nova Scotia where he was given a Canadian grant on the St. John River, upon which Gagetown, New Brunswick now stands.[13] In October 1765 Gage purchased 18,000 acres for £100, located in what is now Oneida county, New York State.[14] Under the system of primogeniture, Gage would not have had these opportunities in England. Therefore by 1774, Thomas had acquired a strong stake in America and the Empire: he wanted to keep the peace. He worked faithfully to support the King and Parliament, at the same time as seeking to bring about harmony with the Americans. Even his enemies regarded him as decent, able and full of good intentions, referring to him as ‘a good and wise man …. surrounded with difficulties.’ [15] In America, Thomas was especially proud of the discipline of his forces and always insisted that his troops were bound by “constitutional laws” and permitted them to “do nothing but what is strictly legal”, even when severely provoked. He recognized an obligation to respect what he called “the common rights of mankind”. Equally, he also saw the need for strict authority and decisive action if the empire was to be preserved. By temperament and principle, Gage was a cautious and conservative person, with an infinite capacity for taking pains. His moderation grew stronger as his responsibilities increased.

I do not propose to dwell upon a detailed historical review of the events in the American colonies during the period of Gage’s residence in New York and Boston, in that they are familiar pages in American history. When Gage moved to New York to become Commander in Chief in 1763 his responsibilities were enormous. He was given five thousand men to hold fast for England the whole eastern half of North America, except New Orleans and the Hudson Bay country, Bermuda and the Bahamas. He had to preserve a vast domain from danger whether from Spanish attack, an attempt by the French to rebuild their empire, indian uprisings, or rebellion by Britain’s own colonists. In addition Thomas had the task of looking after the movement of troops and their families. The soldiers needed to be housed and fed, no mean task, especially when it was necessary to persuade colonial assemblies and officials to provide the food and quarters. Furthermore, many of his duties were of a civic nature. For example, he was compelled to deal with the problem of the French settlers who remained at Detroit and various places in the west outside civil jurisdictions after the peace of 1763. No attempt had been made by the British government to establish a civil government. There was the constant problem with hostile Indians and ‘Pontiac’s War’. Here again, Gage’s skills as a conciliator were well used and one of his most significant contributions was the fact that peace between the British and Indians reigned everywhere by the end of 1765.

In 1763, the British politicians were concerned with the problem of governing an enormous empire. They believed that Pontiac’s uprising was caused in part by the encroachments of colonists upon Indian lands and that their rights should be protected, temporarily, by imperial fiat. Consequently the Proclamation of October 7, 1763 seemed reasonable in England, which forbade the occupation of Indian lands, particularly property lying west of the Alleghenies. They also recognized the need for maintaining a standing army of British regulars in America to garrison the new possessions. However, never had such a large force been stationed in America in peacetime. The national debt in Britain was at an all time high, £130,000,000, a staggering sum in those days, taxes were onerous, and it was the general perception that as the colonists had benefited richly from the expenditures of the mother country, why should the Americans not carry some of the burden of the cost in future? This resulted in the Stamp Act crisis and its repeal. Gage saw the need to provide finance to support the costs of maintaining forces in America, and yet the Stamp Act in 1765 completely took him by surprise, he wrote home to a minister in London ‘I must confess to you, Sir, that during the commotions in North America, I have never been more at a loss how to act.’[16] This was to be Gage’s first real brush with mob rebuttal.

David Hackett Fisher, in his publication Paul Revere’s Ride, has pointed out that two different cultures and values framed the attitudes of the colonists and Thomas Gage. At the outset their principles appear very similar to one another, and not so different from those we hold today. Some of the words they used were superficially the same – such as “liberty”, “law”, “justice”. However, when the meaning of these words are examined, it appears that the values of the colonists and Thomas Gage were in fact very far apart. The Americans’ idea of liberty was not the same as our modern concept of individual autonomy and personal entitlement. Their ideas were not learned from books or learned anachronisms that scholars had invented, but in a deep rooted New England inherited tradition that gave heavy weight to collective rights and individual responsibilities – which after all was one of the reasons that they had left England for a new life in the colonies, and they were not about to place themselves back under the same yoke. The American Revolution arose from a conflict of libertine systems – and land. Following the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770, Thomas took a different view of the colonial problem. He decided that the prevailing tensions rose from a deeper root, specifically in the growth of what he called democracy. As early as 1772, he wrote to his superiors in London ‘Democracy is too prevalent in America, and claims the greatest attention to prevent its increase’.[17]A large part of the problem, he was convinced arose from the vast abundance of cheap land in America – precluded in England under the system of primogeniture. Gage observed that ‘the people themselves have gradually retired from the Coast’ and ‘are, already, almost out of the reach of Law and Government’.

Land tension was exacerbated by the British Government’s passing of the Quebec Act in 1774. This had no connection whatsoever with the events manifesting themselves in the colonies the same year, such as the Boston Tea Party or the meeting of the First Continental Congress in Philadelphia in September. In other words, this exercise was not part of Lord North’s punitive programme – rather that it related to the understanding reached with France under the terms of the Treaty of Paris in 1763, whereby Britain had promised to respect the property of private persons in Canada and to guarantee the freedom of religion – this distinction was missed by the Americans who regarded the law as simply another “Intolerable Act”. Now the resulting ripple of ire extended beyond New England, to Connecticut and particularly Virginia. Lord Dunmore’s war had ended with the Shawnee, Iroquois and other tribes being defeated. They ceded hunting rights in Kentucky to the Virginians and unhindered access to and navigation on the Ohio River. Within six months the Transylvanian Company sent Daniel Boone to blaze a trail through the Cumberland Gap into the blue grass country of Kentucky. The Quebec Act effectively aligned the Canadian boundary south to the Ohio west to the Mississippi River, thus stemming the flow of Virginians across the mountains. This cut off Virginia’s claims (whose western ambitions were limitless) and threatened to spoil the hopes and schemes of numerous land speculators, including George Washington, establishing a highly Crown-controlled government with special privileges for the Catholic Church, provoking fears that the French Canadians rather than the Protestant Virginians would rule the Ohio Valley. This sparked dread in their hearts. It was the repercussions of the Quebec Act in the American colonies that would return to haunt Parliament.

In April 1770 the British Government repealed the Townsend Acts, with the exception of the tax on tea. Three years of relative quiet began in the fall. As he had served nearly twenty years in America without vacation, Gage felt that he could apply for a leave of absence ‘because of affairs of my family which require my presence for some time in England’.[18] Doubtless he wished to see his brother, and meet his sister in law; Margaret was eager to meet her husband’s English relatives, and the both of them would have been keen to visit their children in school. Besides it would be pleasant to take in the sights of London, enjoy the English countryside, to renew old friendships, and to learn what was current in British politics. Permission was finally granted and Thomas and Margaret went home, embarking upon Captain Effingham Lawrence’s Earl of Dunmore on June 8, 1773, where he was greeted triumphantly.

Their departure was sincerely regretted, since it was very possible that General Gage might not return. The unequivocal esteem in which Gage was held, was clearly demonstrated at a dinner given in New York in his honour by the mayor and council, the day before the Gage’s departure. By way of a token of the affection and respect in which Thomas was regarded, he was granted the Freedom of the City of New York. This gold Freedom Box is of extraordinary interest considering that gold work from the American colonies is extremely rare. The Freedom Box was initiated under the Mayor of New York, Whitehead Hicks. Minutes of a meeting of the city’s Common Council on May 20, 1773 record ‘Communicated to this Board that General Gage Intends shortly to leave this province for Europe, and that as his Conduct had been generally approved of by the Inhabitants of this City, therefore proposed that this Board Should Address him & the same time prefer him with the freedom of this Corporation, the seal whereof to be Enclosed in a Gold Box. This Board therefore agreeing in Sentiment with Mr. Mayor ORDER’D that an Address & freedom be prepared Accordingly’. This gold box, embossed and chased with the pre-revolutionary seal of New York, was made by Otto Paul de Parisien, a goldsmith, believed to have arrived in Philadelphia from Berlin in October 1753, subsequently moving to New York, where he took the Oath of Colonial Naturalization on January 18, 1763. Recently, the Parisien family provided correspondence to indicate that there may not have been sufficient gold in the colonies to make up a Freedom Box, by family tradition the goldsmith and his wife melted down their wedding bands, to provide the difference! This is a remarkable colonial survivor, the only other known colonial Freedom Box appears to be that made by Charles Le Roux for presentation by the City of New York in 1735 to Andrew Hamilton, the Philadephia attorney, for his ‘learned and Generous defence of the Rights of Mankind and Liberty of the Press in the Case of John Peter Zenger’ and now in the Pennsylvania Historical Society. The Freedom Document still hangs at Firle Place, the Gage family ancestral home in Sussex, England. General Gage responded to this moving gesture with a gracious letter of thanks ….’I esteem myself highly honoured by your enrolling my Name in the List of your Citizens and I accept your present with gratitude, as a Memorial of your Affections, and as such I shall ever carefully preserve it. It is my Ardent Wish, that your City may increase & prosper & that its Inhabitants may continue a flourishing & happy people, to the End of Time.’

After the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773 Thomas Gage was sent back to America as the best man to control the situation. He was also made Governor of Massachusetts, replacing Thomas Hutchinson, arrived in Boston aboard Captain Bishop’s H.M.S. Liveley on May 13, 1774. Margaret followed later, initially spending some time with her family in New York. Finally she left for Boston under the escort of Major Shirreff, arriving there on September 12. She found her husband virtually besieged. Parliament had responded to the Tea Party with great and misdirected energy by instituting forceful measures, a series of laws called “The Coercive Acts”, and as already mentioned were dubbed the “Intolerable Acts” by the colonists. The port of Boston was declared closed to all trade and the Royal Navy was dispatched to ensure that no ships sailed in or out of the harbour. Over two hundred years after the event, it is easy to see that the Boston Port Bill and the demand of the British Government that payment be made for the ruined teas, was a stupid measure. Parliament also endeavoured to limit the power of popular institutions and increase executive power. Henceforth, the Royal Governor, not the assembly would choose members of the Council. Gatherings where ‘the very dregs of the people’ thus frustrating the will of Parliament, were outlawed. As Governor, Thomas Gage came to proclaim the solemn league and covenant as a traitorous assemblage, proclaimed as for ‘the encouragement of virtue and the suppression of vice’. While these were measures aimed at diffusing resistance, they instead provoked outrage and offence.

Gage’s position was very different from ten years earlier. In September 1774 his friend James Abercrombie wrote from London: ‘I am extremely sorry that you are so situated [in Boston], for little honour or credit is to be got, but your all is at stake. If you succeed in bringing about a reconciliation, the Cockpit plume themselves; if force to force is necessary it may ridiculously be called a massacre …. and your name may be unjustly execrated.’ Force prevailed, but it was not the colonists who were massacred.

While the port of Boston was closed, Thomas Gage moved his headquarters to Salem. On June 5, 1774 he leased The Lindens, in Danvers, built in 1754 by the merchant Robert ‘King’ Hooper, and considered one of the most important colonial mansions in the country, notable for an unusual façade in which the wood boards are cut and finished with sand-embedded paint to resemble ashlar masonry blocks. Thomas left on September 12, warned by Captain John Montressor that he was personally in danger in the neighbourhood of Salem, and moved back to Boston.

General Gage’s tenure in Boston was unappreciated at home: his forces were insufficient, ill-supplied and demoralised, he lacked the authority to deal with constant irritations such as basic powers of arrest and in his day to day existence he found himself in a viper’s nest of spies. In March 1774 If Gage really believed that he could police Boston with four regiments in March, on his return to Boston by the end of August he had no illusions. He realized the situation was grave. Gage constantly pressed for reinforcements. In a private letter to Viscount Barrington dated November 2nd he wrote ‘… if you resist and not yield [to American demands], that resistance should be effectual at the beginning. If you think ten thousand men sufficient, send twenty, if one million is thought enough, give two; you will save both blood and treasure in the end. A large force will terrify, and engage many to join you, a middling one will encourage resistance, and gain no friends. The crisis is indeed an alarming one, & Britain had never more need of wisdom, firmness, and union than at this juncture.[19] By December when the colonists seized the arsenal in Fort William and Mary, and Gage wrote home to Lord Dartmouth, the Colonial Secretary: ‘I hope you will send me a sufficient force to command the country … affairs are at a crisis and if you give way it is for ever’. His repeated requests were met with derision and scorn in London. Indeed, in November when Gage went further, and urged that the Coercive Acts (which he had proposed) should be suspended until more troops could be sent to Boston, the idea caused consternation in London. The King himself angrily rejected Gage’s advice as ‘the most absurd that can be suggested’[20]

What did Thomas do, beyond making his military preparations to meet the crisis that arose in the late summer of 1774? He took great care not to force an armed clash; he reported the situation diligently to Barrington and Dartmouth in London; he displayed the prudence and coolness for which he was so well known; he was not only polite to delegations of Americans who sought him out, he was even gracious. He worked with the officials of Boston to prevent clashes between his men and the townspeople. This soldier who hated war did not wish to use force against the Americans, except as the last resort. If there was to be armed conflict, he would let the Americans or the British government instigate it.

His purpose was to remove from Yankee hands the means of violence until such a time when cooler heads would prevail. To that end, I believe General Gage’s thought process and plans were misunderstood. What he proposed was to disarm New England by a series of small surgical operations – meticulously planned, secretly mounted, and carried off with a careful economy of force. His object was not to provoke a war but to prevent one, as a seasoned soldier, he had witnessed enough bloodshed and his priority was to avert more. New England’s Whig leaders were vulnerable to such a strategy. While there were many weapons in the hands of the colonists, there were not enough for determined struggle against the King’s troops, and there was no easy opportunity for re-supply. Few firearms were manufactured in New England and gunpowder had to be imported from abroad. The plan had one major weakness. It could only succeed by surprise. And Gage had completely underestimated the temper of New England and a fundamental difference in perception and attitude to the ownership of powder.

On September 1, 1774 Thomas set his plan in motion. His first step was to seize the largest stock of gunpowder in New England. It was stored in a magazine called the Provincial Powder House, six miles northwest of Boston. He dispatched one of his most able officers, Lieutenant-Colonel George Maddison, and with 260 picked men, two hundred and fifty barrels of powder were transported under cover of darkness, and carried by boat to Boston, a highly successful mission. The Loyalists viewed this supply as the King’s powder. But most people in Massachusetts believed that it belonged to them – thus removing it was similar to lighting a touch paper!

Bolstered by the successful strategy of the earlier mission, though astonished by the rising in the countryside and anger he had awakened, Gage became cautious: a similar strike to seize munitions in Worcester was deferred while he marked time. In due course, Gage decided to repeat this operation and to remove the military stores in Concord. His plans for secrecy of the exercise were again undermined. Paul Revere spread the word as the British troops moved out Boston in the early hours of the morning of April 19, 1774, and as they crossed Lexington Common, it seems John Hancock and Samuel Adams were taken by surprise, who were staying in the town. When they escaped, together with incriminating documents, a diversionary shot was fired from the tavern window – the first shot of the revolution. By the time the British troops reached Concord, an armed militia of 400 was standing by. Following a skirmish at the North Bridge, the British Regulars prudently began a retreat to Boston.

Word of the fighting spread quickly across the Colonies. Boston was now truly under siege, and Gage worried that the militiamen would storm the city. William Howe, considered one of the most promising young officers in the British Army, had served with distinction under General James Wolfe during the French and Indian War, came to Boston with re-enforcements and two other major generals in May 1775, to bolster Gage’s besieged command. The hills surrounding Boston were key to military strategy. A patriot entrenchment built high enough on Charleston or Dorchester Peninuslars would stand out of reach of cannon aboard the warships in the harbour and could dislodge the British from Boston. Learning of a British initiative to fortify Dorchester Heights, provincial leaders resolved to hold Bunker Hill on the Charleston Peninsular and in the darkness of the evening of June 16, 1775 Col. William Prescott led 1,200 Massachusetts and Connecticut men out of Cambridge to build a redoubt. Through miscommunication or ignorance of the terrain, Prescott’s men by-passed Bunker Hill and instead dug in on Breed’s Hill. The British reacted swiftly. In the early afternoon of June 17, 1775, barges and longboats filled with scarlet clad regulars made their way across Boston Harbour and came ashore at Moulton’s Point. Col. Prescott told his men not to fire ‘until you see the whites of their eyes’. Through billows of smoke, over fences and treacherous footing, General Howe’s infantry marched, no sooner had the first attack been turned back, than the British re-grouped and marched forward again, finally taking the position on the third assault, though at the cost of catastrophic casualties. Of Howe’s 2,200 ground forces and artillery engaged in the battle, nearly half (1,034) were killed or wounded. Of an estimated 2,500 to 4,000 patriots engaged, 400-600 were casualties.

General Gage was recalled to London in October 1775, on the pretext that he was required in England to help lay plans for major operations in 1776. Margaret has left earlier, she was sent to England by her husband in the summer of 1775, in part because she was pregnant, and no doubt he was concerned for her safety and well-being in the now politically charged and deeply unpleasant atmosphere of Boston. She sailed in the transport Charming Nancy, with sixty widows and orphans and 170 severely wounded British soldiers who were bound for the Royal Hospital at Chelsea. It was a terrible voyage. When the ship put in to the English port of Plymouth for a replacement mainmast, a correspondent wrote that ‘a few of the men came on shore, when never hardly were seen such objects! Some without legs, and others without arms; and their cloaths hanging on them like a loose morning gown, so much were they fallen away by sickness and want of proper nourishment … the vessel itself, though very large, was almost intolerable, from the stench arising from the sick and wounded.[21]Gage was never to return to America. When General Howe took over as Commander in Chief, this reflected a marked change in tenor and a significant watershed concerning the future of the colonies: the person who at heart had the greater interest to finding a peaceful and conciliatory way forward was replaced by those purely of a professional military mindset. The rest is history.

For a while after their return, Thomas and Margaret lived with their family at Park Place in London, until in 1799 Gage purchased a house at what is now 41 Portland Place. Among their neighbours was John Montresor, four doors down who was George III’s Chief Engineer in America and his map of New York surveyed in 1775 and dedicated to Thomas, is now at Firle Place. Due to the loss of his pay and perquisites as Commander in Chief, Gage could not probably afford a county home. However, he and his family were welcome and frequent guests at Firle Place, and where too they often brought their friends such as Frederick Haldiman and Thomas Hutchinson. Thomas enjoyed a warm and close relationship with his brother, William Hall, whose children all died. Thus, Thomas and Margaret’s eldest son, Henry inherited, to become the third Viscount Gage. Thomas died of bowel cancer at Portland Place on April 2, 1787 and was laid to rest quietly in the family crypt at St. Peter’s, Firle.

Margaret survived Thomas by 37 years, continuing to live at Portland Place, and finally moving to Albemarle Street, presumably to be closer to her son, Henry living in Arlington Street. She died on 9 February, 1824 having attained the remarkable age of 90! and was also interned in the family vault at Firle. Margaret enjoyed the company of her children after Thomas’s death, and indeed of her brothers and a number of cousins who came to England regularly or, as Loyalists, had left America after the revolution to settle in Britain. Her elder brother Samuel, came to London in 1783, where he established himself as a merchant. Another brother, Stephen, whom Thomas regarded as one of his closest friends, like Samuel had been an indispensable member of his staff in Boston. As Gage became more and more entrenched in Boston, it is of interest to note that he increasingly surrounded himself with his kinsmen, whom he felt he could trust the most. After his death, Stephen was employed by Margaret to oversee the properties in New York State and the West Indies, thereby insuring that she had a comfortable income to live on for the remainder of her life. Other cousins, such as Philip Van Cortland, came to settle in Sussex with the help of the Gage family there. He lived in Van Cortland Manor House in Hailsham, and there is a memorial to him in St. Mary’s Church, where he is buried. While on the subject of the Loyalists, it is perhaps worth briefly making a comment vis à vis this largely overlooked aspect of the aftermath of the war by simply quoting Charles Halsten Van Tyne’ introduction to his publication, The Loyalists in the American Revolution: ‘The formation of the Tory or Loyalist party in the American Revolution; its persecution by the Whigs during a long and fratricidal war, and the banishment or death of over one hundred thousand of these most conservative and respectable Americans is a tragedy but rarely paralled in the history of the world.’

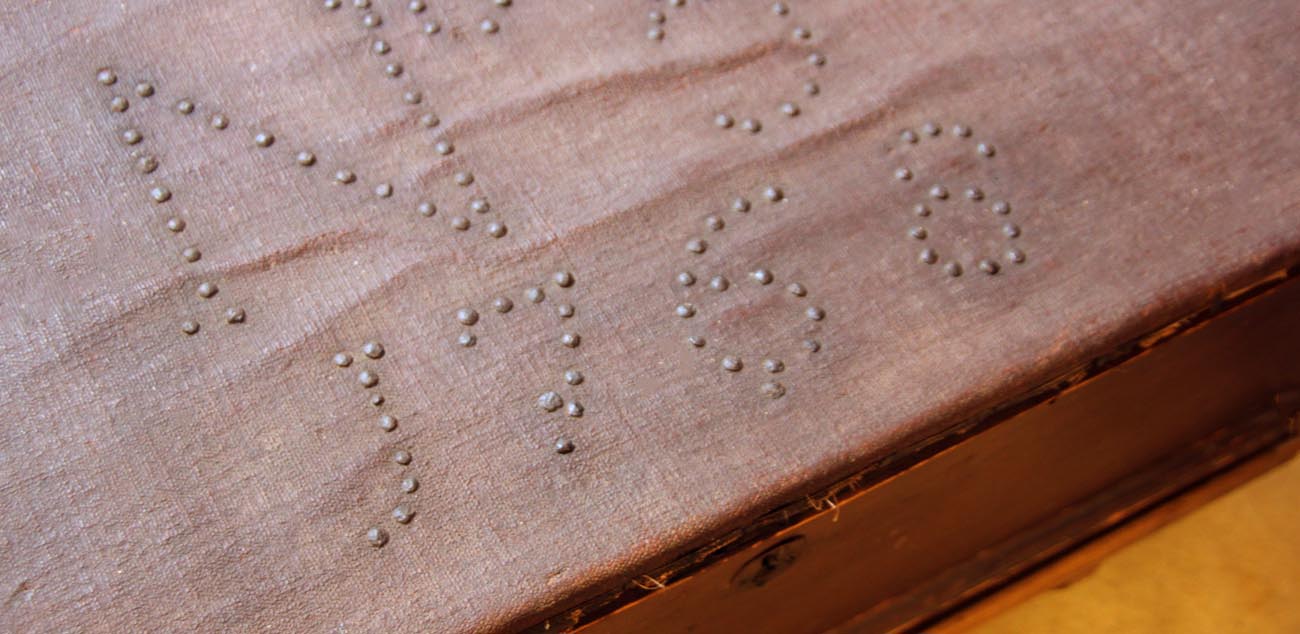

At the close of each year of his command, Lieutenant General Thomas Gage classified his correspondence according to the place of origin, tied the folded letters with red tape, and filed them in pigeon-holes within a pine chest which was then labelled with tack work. When he sailed home to England at the end of 1775, he took with him twelve red-stained chests containing more than 21,000 manuscripts. They include correspondence from his headquarters in New York to the various post commandments across eastern North America, with the colonial Governors, Indian Superintendents and several Cabinet Ministers, together with his answers, and they chronicle his tenure in Boston. One of these pine chests, studded with the date ‘1768’, is displayed at Firle Place today, purchased at Christie’s auction in New York in 1983 from the noted collection of American decorative arts belonging to the late Mrs. George Maurice Morris. Having fallen into a sorry state, the Morris’s had purchased The Lindens, the house that General Gage had rented in Marblehead in 1774, so they decided to dismantle and move it to Washington DC in 1934. General Gage’s papers are now housed at the William L. Clements Library, Ann Arbor, Michigan, provide us today with much valuable insight. Undoubtedly, Gage made tactical errors and lacked judgement in many aspects. He was in an invidious position, compounded by his own personal shortcomings.

Thomas was often too scrupulous and cautious, so that events caught up with him, I suspect many of his attitudes were dictated by the fact he was a product of the English upper class system, which would have then been even more endemic in determining his mind-set: fundamentally he would have expected to be obeyed. As Tory Lieutenant-Governor Andrew Oliver wrote of Gage that he was ‘a gentleman of an amiable character, and of an open honest mind: too honest to deal with men who from their cradles had been educated in the wile arts of chacene’.[22] David Hackett Fischer has also pointed out, the laws and covenants that New Englanders perceived as the ark of their ancestral rights were seen by Gage to be merely a bizarre form of litigious anarchy. In addition he was too naive. Since he believed in fair play, Gage never curtailed the propagandists in Boston, whose seditious publications undermined morale and spread unrest through the colonies. Likewise his dispatches on Bunker Hill arrived in London two weeks after reports had purposely been sent ahead by the colonists, so that his own account was mis-read, no fault was accorded to the Government, and he was publicly discredited.

This was a time of great personal anguish both for Thomas and for Margaret. At the early stages of his administration Gage had vested enormous resourcefulness and belief into the making of the New World, and establishing stability, security and prosperity for the colonies. He owned land in North America, he had spent the majority of his life there – and indeed was very disillusioned and out of place when he returned briefly to England for a leave of absence in 1773. He wrote to a friend that London seemed as strange to him as Constantinople, or ‘any other city I have never seen’[23]. By marriage he had relatives and friends there, most of his children were born in the North American continent: his life was America. For Margaret too, she must have been wrought by extraordinary mixed-emotions. In a conversation with a friend on the ‘day after that dreadful one’ – the day after Bunker Hill – Mrs. Gage indicated that her own emotions were well described in the touching lines uttered by Blanche of Spain in Shakespeare’s play, King John:

The Sun’s o’ercast with blood; fair day, adieu!

Which is the side that I must go withal?

I am with both; each army hath a hand,

And in their rage, – I having hold of both,

They whirl asunder, and dismember me.

Husband, I cannot pray that thou mayst lose.

Father, I may not wish the fortune thine.

Grandam, I will not wish they wishes thrive.

Whoever wins, on that side shall I lose,

Assured loss, before the match is played.[24]

Margaret made no secret of her great distress. In 1775 Thomas Hutchinson records a conversation, in which Margaret stated ‘she hoped her husband would never be the instrument of sacrificing the lives of her countrymen’.[25] It has long been rumoured that Margaret provided Dr. Warren with the information that the British troops would be moving out the evening of April 19th, 1774 bound for Lexington and Concord, for example as cited in this letter written by Dr. Belcher in June 1775 ‘Entertainment at Providence House, where Madam Gage presided with the social adroitness and tact of a lady of a high New Jersey family, were crowded with uniformed men from both fleet and camp. Yet suspicion attended this lady as not being too loyal to her husband’s party and to the King. It was hinted that the Governor was uxorious, and had no secrets from his wife, who passed word to the spies swarming outside. At any rate whatever was designed in Boston was, it is alleged, known within an hour or two at Medford, at Roxbury, at Cambridge, at Brookline and in every Boston tavern.’ David Hackett Fisher in Paul Revere’s Ride is emphatic that Margaret was the informer. However, I am bound to say, that on the basis I cannot find enough supporting evidence, I would refute this rumour. I believe the facts speak for themselves. Had Margaret felt so strongly for the colonial cause, why did she continue to live in England 37 years after Thomas’s death, rather than return to America? More telling, if Margaret had betrayed her husband, the Gages would not have accorded her full family honour at the time of her death, and interned her in the family crypt at Firle, nor looked after her family in England.

Following American’s victory at Yorktown in 1776, Lord North fell from power and Gage’s enemies were forced to resign from the British Cabinet in 1782. Thomas was subsequently promoted to a full General for his services in the colonies, together with recognition of the fact that his recommendations for sufficient reinforcements had never been heeded. It appears that Thomas continued to be held with affection in America. This may be demonstrated by the fact he was allowed to retain his land in New York State when most Loyalist properties were confiscated. According to General Gage’s bank statements still held by Lloyds Bank in London, even though he had retired from Boston, he continued to collect £1,500 a year as Governor of Massachusetts. His absence was looked upon as temporary.[26]Likewise, Gage’s name remained on the rolls of the celebrated American Philosophical Society of Philadelphia, of which he became a member on December 20, 1768, until his death.[27]

Effectively, Thomas Gage was a victim of circumstance: in the wrong place at the wrong moment! This became evidently clear to me when my cousin, the eighth Viscount Gage and head of the family, and myself were invited to participate in the re-enactment of the 225th anniversary of the skirmishes of Lexington and Concord, in April 2000. Many of the re-enactors are historians, so there proved to be a serious aspect to this experience. Consequently, I became the more focused upon the fact that the corollary of primogeniture – not so much taxation – was the underlying and most compellingly emotive and divisive issue that led the colonial quarrel into armed rebellion. The Quebec Act of 1774 effectively curtailed the availability of land in the context of the New World land rush. Now, not even the British government could stand in the way of an unstoppable westward train under a full head of steam. No wonder those young men streamed out on Lexington Common early in the morning of April 19, 1774, willing to risk their lives for their stake to land – that would have been unattainable to them, back in England. That evening we sat in General Gage’s pew in the Anglican Old North End Church, Boston for a celebratory service. The church was lit by candlelight, music was provided by the fife and drum. Also seated in the congregation were the descendants of Samuel Adams and Paul Revere. It was a moving moment: we happily introduced ourselves afterwards and shook hands!

References:

Alden, John Richard, General Gage in America: Being Principally a History of His Role in the American Revolution, 1948, Louisiana State University;

Fischer, David Hacket, Paul Revere’s Ride, 1994, Oxford University Press;

Ellis, Joseph J., The Quartet, Orchestrating the Second American Revolution, 1783-1789, Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2015.[1] Fischer, p. 34

[2] Fischer, p. 34

[3] Fischer, p. 34

[4] Alden, p. 42

[5] Fischer, p. 35

[6] Alden, p. 53

[7] Alden, p. 105

[8] Ellis, p. xi

[9] Alden, p. 57

[10] Alden, p. 61

[11] New York Historical Society Collections, 1884, Kemble Papers, Vol. II

[12] Copley-Pelham papers

[13] Alden, p. 70

[14] Alden, p. 71.

[15] Fischer, p. 36

[16] Fischer, pp. 37 & 38

[17] Fischer, p. 39

[18] Alden, p. 192

[19] Alden, p. 219

[20] Fischer, p. 50

[21] Fischer, p. 290

[22] Fischer, p. 41

[23] Fischer, p. 40

[24] Alden, pp. 248/249

[25] Fischer, p. 96

[26] 1776:The British Story of the American Revolution, National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, 1976, No. 55

[27] Alden, p. 68