Joseph Gage – The Gamble

The Great Mirror of Folly, satirizing John Law and his Mississippi Company and the South Sea Bubble.

In much the same way as Martin Murphy came across Joseph Gage through researching his family history, serendipitously we encountered yet more colourful drama in the life of this charismatic character. In fact the story which follows, and the leading actors in it, inspired the imagination of no lesser figures than Alexander Pope and Daniel Defoe – two of the most perceptive and brilliant writers of their day. It comes therefore as something of a surprise that this murky episode has been totally neglected by historians. We stumbled across it by pure chance because our own ancestor, Daniel Mackenzie, was a first cousin and close friend of the Gray’s Inn lawyer, Kenneth Mackenzie, working for both him and Kenneth’s sister-in-law, Frances Herbert, 4th Countess (and 1st Jacobite Marchioness) of Seaforth. Kenneth was to become profoundly entangled in Gage’s financial and legal affairs, and Frances’s granddaughter, Catherine Caryll, was to be briefly married to Joseph Gage.

Kenneth Mackenzie was the second son of George Mackenzie of Gruinard, a grandson of the 2nd Earl of Seaforth. He managed the affairs of William, the 5th Earl (and 2nd Jacobite Marquis) of Seaforth, together with those of his Herbert wife and in-laws (Ladies Anne, Frances and Mary) over the course of three decades. Although Kenneth’s roots were in the remote north-west coast Highland estate of Gruinard, he led the life of a sophisticated London lawyer with extensive English estates and the highest social connections. Of Earl William’s grandfather, the Jacobite Duke of Powis, Kenneth said “most of his family have a more or less dependence on me” – a statement which was to take on a wider meaning when he actually came to marry the Duke’s daughter, Anne. It was this relationship that drew him into the web of intrigue which surrounded Joseph Gage and his circle in the 1720s.

The most challenging legal suit which preoccupied Kenneth, and threatened his own wealth as well as that of the Herberts, began in 1719. We learn that the instigator of this affair was George Mackenzie Quin, by now a diplomat working on behalf of the British government at the French court, who had already had a particularly flamboyant career. Mackenzie Quin’s early life could very easily have come out of the pages of a novel by Alexandre Dumas. As a law student in Paris he had been implicated as a spy and for some three years from mid-1702 he was imprisoned in the Bastille. From George’s own words we learn that it was a specific condition of his release from the Parisian fortress that he “swear to not divulging anything he had seen or heard” whilst inside. The intriguing significance of this is that George was in the Bastille for over a year alongside the “Man in the Iron Mask” – who died there in November 1703. After then serving successively as British Envoy to the court of King Augustus II of Poland and as British Resident to the court of Tsar Peter the Great in St Petersburg, George was based in Paris, where he served as Secretary to the Earl of Stair, the pro-Hanoverian Ambassador to the Court of Versailles. Here, once more, we find this devious character acting as a Jacobite double agent: one source informing us that George had been operating as an unofficial ambassador to Peter’s Court – not for the British Government, but on behalf of the exiled King James’s Queen, Mary of Modena – and when we encounter him again in the 1720s we find the likely veracity of this source confirmed: by then he had acquired friends in the Parisian suburb of Chaillot – the location of the convent to which Mary had permanently retired in the years before her death in 1718.

No doubt as a result of their close Jacobite and Mackenzie family connections, in 1719, and with disastrous consequences, George encouraged Kenneth’s wife, Lady Anne, her niece, Lady Mary Herbert and the latter’s business partner, the self-styled “Count” Joseph Gage (all living in Paris at the time) to invest in the Mississippi Scheme, which had just been set up by the new French Finance Minister, the infamous Scot, John Law. Here we chanced upon the ensuing, somewhat pantomime episode, part of which Martin Murphy himself recounts in his The Duchess of Rio Tinto: the Story of Mary Herbert and Joseph Gage.

By August 1717 Law had established for himself a position of immense influence with the French Regent, Philippe, Duc d’Orléans. The Regent Orléans was desperate to make amends for his predecessor, the Sun King’s wars – wars which had had such a crippling effect on France’s finances – and so allowed his Scottish protégé to establish the Company of the West, better known as the Mississippi Company. The Company was given the right to all trade between France and its Louisiana colony for 25 years, to maintain its own army and navy, to mine and to farm. As managing director of the Company, Law effectively ruled over half of America. Exaggerating the wealth of Louisiana by means of a highly successful marketing campaign, in 1719 Law encouraged wild speculation on the shares of the Company. Tantalising reports appeared in France’s official newspaper, the Nouveau Mercure; correspondence described a land of milk and honey in which the climate was temperate, the soil fertile, the woods overstocked with trees suited to building and export, and the countryside populated with wild yet benign “horses, buffaloes, and cows, which however do no harm but run away at the sight of men.” In this Garden of Eden, said an article published in September 1717, the soil bulged with seams of gold and silver ore; other valuable minerals – copper, lead and mercury – also awaited exploitation. In fact the Company’s shares became so popular that they sparked a need for more paper bank notes to pay out the investors. The profits for the initial investors were breathtaking.

It is only too appropriate that this was the age which gave a new word to the French language: millionaire. Journalists revelled in the frenzied, get-rich-quick atmosphere, and among the most notorious of these speculators were Lady Mary Herbert and her lifelong admirer and business partner, Joseph Gage. Their roller-coaster partnership was to last all their lifetimes – although Lady Mary, ultimately more interested in money than anything else, managed to resist “Beau Gage’s” desire to marry her.

In the years following the 1715 Rising, Mary and her aunt, Kenneth Mackenzie’s clandestine wife, Anne Lady Carrington, had travelled frequently between Paris and London, sometimes carrying messages to English Jacobites from the Earl of Mar: Mar was the Pretender’s chief adviser, and thought highly of her. Anne survived her husband, the 2nd Viscount Carrington, by almost 50 years after his death in 1701. She had carried the train of Queen Mary of Modena at the Coronation of 1685, but it was all downhill after that. Her fatal association with her domineering niece, Lady Mary Herbert, was in her old age to bring her to the verge of destitution.

The speculations of Mary and Joseph in Paris had been funded by loans from the Irish pioneer economist and one of Paris’s most successful private bankers, Richard Cantillon. In partnership with Law and Cantillon Gage acquired the rights in 1719 to a plot of 16 square leagues bordering the Ouachita River to the west of the Mississippi, in what is now the state of Arkansas. Around a hundred settlers, including carpenters, mine-workers and gardeners were enlisted to prospect for minerals and grow tobacco. In one periodical Defoe commented: “Beau Gage has gained three hundred thousand pounds sterling by the stocks.” In October 1719, the English ambassador, Lord Stair, forwarded letters from Joseph to the Lord Chancellor and Prime Minister, offering to transfer his spectacular gains to London in return for a peerage and exemption from the law which debarred Roman Catholics from purchasing estates. Stair described him as a Croesus: “He reckons himself already worth 50 thousand a year, and will not be satisfied till he has 100 thousand. I wish a good share of these riches would be showered down some Thursday night in Downing Street”. Gage was even reputed to have attempted to buy the island of Sardinia and the Crown of Poland. Apparently spurned in Poland by Augustus the Strong, Alexander Pope, in his Epistle to Bathurst, was inspired to satirise Mary and Joseph for betraying their class and adopting the morals of the market-place:

“The Crown of Poland, venal twice an age,

To just three millions stinted modest Gage.

But nobler scenes Maria’s dreams unfold:

Hereditary Realms, and Worlds of Gold.

Congenial Souls! whose life one Av’rice joins,

And one fate buries in th’Asturian mines.”

In his own explanatory note on these lines, Pope described Joseph and Mary as “two persons of distinction, each of whom in the time of the Mississippi despised to realise above three hundred thousand pound: the gentleman with a view to the Crown of Poland, the lady on a vision of a like nature.” The bid for the Polish Crown has been viewed ever since by commentators as embellished poetic licence on the part of Pope; however, the connections with Mackenzie Quin – who had been close to King Augustus’s son and was later to serve as a diplomat at his court in Poland – strongly suggest that there was rather more to it.

Law’s pioneering note-issuing bank thrived so long as he kept careful control of the numbers of notes issued. However, after his Banque Générale became the Banque Royale in 1718, with royal ownership and no shareholders to ask awkward questions, the bank became less regulated and the temptation to print too much paper money too quickly became virtually unchecked. The Regent and his advisers were forced to admit that the number of paper notes being issued by the Banque Royale exceeded the value of the amount of metal coinage it held. One longstanding supporter of the scheme, in particular, began to fear the worst.

When Lord Stair, accompanied by his Secretary, Mackenzie Quin, first arrived in Paris in January 1715, his old countryman and friend, Law, was the first person he visited. However, a seasoned and often unlucky gambler, and by now sceptical of every price rise, Stair became increasingly distrustful of and antagonistic towards Mississippi speculation. His scepticism proved correct: the reality concealed beneath the mask of alluring misinformation was that the American colony was struggling to stay alive. The adventurers found themselves in a miserable, hostile territory in which the very fight for survival overshadowed any attempt to prosper. The immigrants were racked with scurvy, dysentery, malaria and yellow fever. There was also the ever-present danger of hostile Indians, who needed constant bribes to keep them friendly. Another two centuries would have to pass before the true wealth beneath the soil was found – not in silver, gold or emeralds, but in oil.

Angry investors in the Rue Quincampoix outside John Law’s Bank. Engraving by Antoine Humblot.

Having bought Mississippi stock at the low of 150 livres, when the share price rose by August to over 2,000, Cantillon had realised just in time that the bull market was little more than smoke and mirrors – involving ever-increasing quantities of paper money. Feeling that a crash was both inevitable and imminent, he cashed in. His profit from these few weeks’ exposure was reputed to be £50,000. Leaving Paris with his winnings, he went on tour in Italy to enjoy the sights and invest in art. Law similarly fled to the Low Countries later that Summer, with the connivance of his patron the Regent. Although George Mackenzie Quin was also wise enough to get out in time, in the three months from March to May 1720 – when most investors had begun to be aware of the warning signs – Lady Mary remained stubbornly sure that the livre would continue to appreciate. She, her aunt Carrington, Gage and the Herberts borrowed vast sums which they converted into French banknotes in the forlorn belief that the price of silver, in relation to notes, would have dropped even more by the time the loans were due for repayment. Mary was as rash in currency speculation as she had been in share dealing.

The “Bubble” famously burst on 22 May 1720, when Law’s opponents tried to redeem their notes in such numbers that the bank had to stop payment on its paper notes. Both Joseph and Mary, as well as Mary’s unfortunate aunt, were left holding valueless shares and banknotes, and owing George and Cantillon enormous sums. In 1720 Lady Anne owed Cantillon £20,000 sterling and Lady Mary £43,851. In total the Herbert family were indebted to the sum of £170,000 and faced ruin. They blamed their predicament on their creditors, whom they duly sued for fraud and usury. The legal and personal challenges which Kenneth and his family were now left to deal with involved a web of accusations and counter‐accusations concerning murder, sodomy, bigamy, theft and fraud – and lasted for decades. As so brilliantly satirised by Pope, the grands seigneurs, who by tradition were supposed to be above commerce, had now tarnished their hands from rummaging in the greasy till, and their ostentatious luxury and arrogant indifference to public opinion lit a slow fuse of popular resentment, ultimately culminating in revolution seven decades later. The principle of noblesse oblige had been abandoned and the established ruling class exposed as greedy and corrupt.

The Herberts’ Paris lawyer, Christopher Balfe alleged, as he also did against Cantillon, that George Mackenzie Quin had charged usurious rates of interest on the loan that he had made to them. George then counter-sued the Herberts in 1725 for misappropriation of share certificates which he had deposited with them while he was absent from France. Gage, George declared, “was attached to the Demoiselle Powis by a singular affection that was public knowledge” and he blamed him for the humiliation to which the Herberts had been subjected – which had made “un éclat dans le public”. George was baying for retribution and matters intensified even further when he went on to contend that Gage and Balfe had bribed James Byrne, a young Irish lieutenant in Rothes’s regiment, to attempt to kill the diplomat while he was travelling through the forest between Versailles and Paris.

Aerial view of the gardens of Versailles from above the palace, showing beyond part of the forest where Joseph Gage and Christopher Balfe allegedly attempted to have George Mackenzie Quin assassinated.

After the assassination attempt failed, Gage and Balfe now had recourse to conspire with another enemy of George to bring a bizarre charge of sodomy against him – an offence which was then theoretically punishable by death. This adversary of Mackenzie Quin had even more pressing reason for wanting to be rid of him: in 1719, when he was about to leave France on a secret mission to Italy on behalf of the Regent, the Scottish diplomat had deposited 429 Mississippi share certificates for safekeeping with his neighbour in the Parisian suburb of Chaillot, a certain Abbé René Duval, whose brother, the Abbé Pierre-François, was schoolmaster there. Leaving these shares in René’s hands turned out to be a major error of judgment, because on his return to France, the Abbé refused to return them and George was forced to take his former friend to court. George argued that the Abbé had sold his shares and invested the proceeds in real estate, laundering these operations by purchasing land and property through the use of third parties. It would appear that Duval opted to go to gaol rather than pay up.

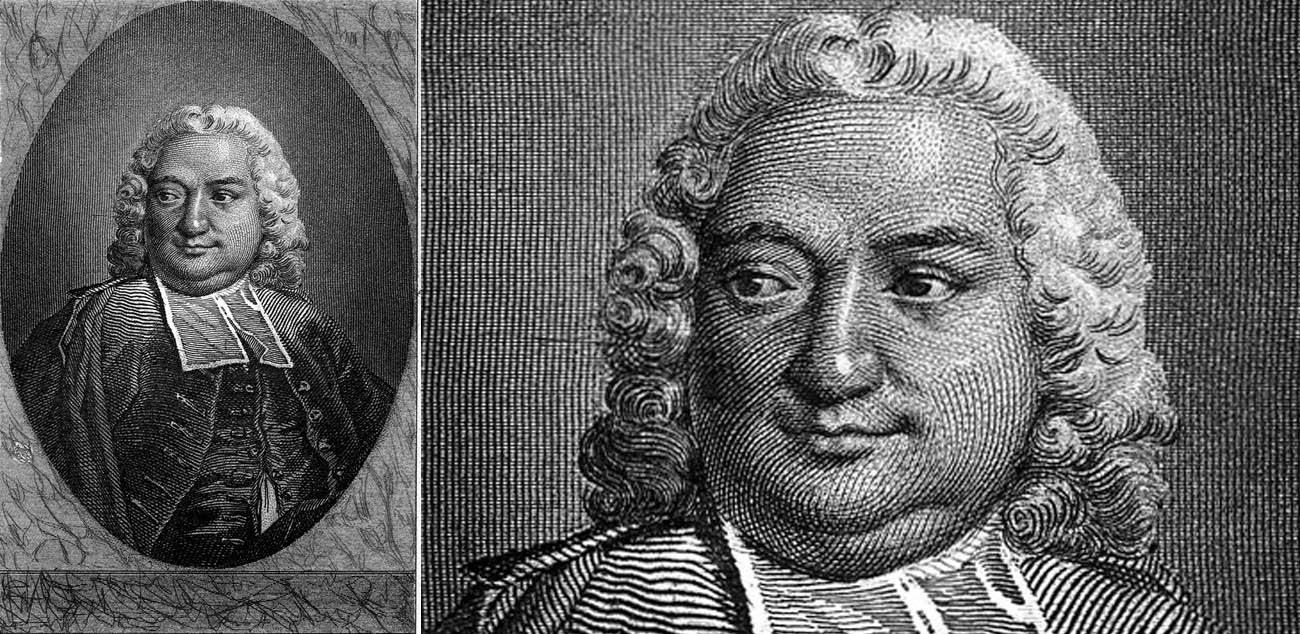

One of the two Duval brothers – the Abbé Pierre-François Duval Desfontaines.

Prison, after all was hardly daunting for a man like the Abbé René Duval, for whom it was easy to buy privileges and make bribes. Comfortably installed in the Châtelet prison in November 1723, he was joined by his brother, Pierre-François, and enjoyed all the comforts a decent hotel might offer. And that remained to be the case for Pierre-François when he was re-imprisoned in 1724 “for sodomitical behaviour” – for we know that his prison meals were being brought in from a restaurant by his resident valet. We also know that the Abbé Pierre-François was closely associated with Voltaire – and in fact we find Voltaire procuring his release that same year. The lengthy police reports on Pierre-François reveal that he had made a great deal of money from speculating in shares and that he sold his library (containing a collection of “sodomitical” prints) to one “Law”. Given all of the other associations, the latter must clearly be John Law and the strong implication is that George had been responsible for the imprisonment of both of the brothers.

And the story gets yet more colourful. Some time in the year 1726 it seems that the Herbert-Gage syndicate had been lucky enough to secure the service of one of Cantillon’s former partners and the widow of another partner, both of whom had inside knowledge of their master’s dealings and were willing to provide incriminating evidence against him.

René Duval’s mistress, Mlle Marie Vergnault, who had undoubtedly benefited from the profits of George’s pilfered Mississippi shares, undertook the task of recruiting “witnesses” and taking down their sworn depositions. In one such statement, the Mademoiselle herself, whom the lawyers euphemistically described as living in “a close relationship” with the Abbé for 15 years, claimed he had seen George “dans une posture infâme avec son nègre” – his black slave. Most of these “witnesses” had never seen George. Not surprisingly, the evidence of these amateur criminals was so contradictory that the case collapsed in a series of mutual reproaches and denials.

Aubrey Beardley’s grotesque The Cave of Spleen, an illustration for Alexander Pope’s The Rape of the Lock – in which the intimate friend of the Caryll family bitingly satirised the world of Cantillon, Mackenzie Quin, the Herberts and Gage.

The vendetta between Balfe and George Mackenzie Quin did not however end there. It dragged on acrimoniously for years. Mackenzie Quin appealed against the court ruling which had cleared Balfe of the charges of defamation and attempted murder, but in 1740 the court found against him, obliging him to pay even heavier damages. George’s desperate state can be gleaned from his persistent memoranda to the British Government in the 1750s, pleading for compensation for the huge financial loss he claimed to have suffered through his service in the interests of the Hanoverian cause. There is no suggestion that he ever recovered his loss, for he wrote to the Prime Minister, the Duke of Newcastle, in 1757: “To me, My Lord Penury can be no Ignominy, who justly ought to be so opulent as any of my Class, in the Service of the Crown.”

The lawsuits drove Cantillon from Paris to London. Cantillon was to go on to turn his attention in London to South Sea shares – and a similarly spectacular fortune. Even Isaac Newton blindly took part in the South Sea speculation in England and when asked for advice on the subject is said to have responded that while he could calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, he could not do the same for the madness of the people. He died in 1734 in mysterious circumstances. His town house in Albemarle Street was burned to the ground, and what was alleged to be his corpse (conveniently headless) was found in the ashes. The financier’s mysterious death has been the subject of much speculation. Was the whole affair subterfuge, constructed by Cantillon himself so that he could escape?

As for the Herberts, the court ordered them to compensate Mackenzie Quin to the sum of 60,000 livres. To evade the court order, Lord Powis took refuge in England, while Joseph Gage, Mary and her aunt went into hiding. A series of letters survives which record how over the course of 15 years Anne Carrington kept up a correspondence with her lawyer husband in London, pleading for a final allowance that might see her out of all her troubles. In the Autumn of 1726 Anne complained that for the past three months she and her niece had been on the road, “constantly travilin from plas t plas like the wandring Jue, fixt noewhere.” On another occasion, writing to her husband from Spain, she complained: “I am hartily tired of my way of living, rambling from one place to another.” Lady Mary also wrote to Kenneth from Madrid: “Neither Lady Carrington nor I had a ragg a cloathes but what have been given to us out of friendship, not to call it charity. She is now quite naked, not a smock to her back, nor a nightgown … a great greef to me, and a great shame to the family”. When Kenneth died in 1729 and the two women lost their staunchest supporter, Lady Mary challenged his will, thereby beginning yet another round of unresolved litigation.

The next we hear of Kenneth’s unfortunate widow is in 1745 when Prince Charles Edward paid a courtesy call to Lady Carrington on the eve of his famous expedition to Scotland. As she wrote to her sister, Lady Nithsdale: “The Prince came to see me. He is very gracious and affable, spoke of you with a great deal of esteem.” According to Horace Walpole, the Prince found Anne in so reduced a state that, for want of suitable clothes, she had to receive her royal visitor in bed, and he felt obliged to give her his overcoat and spare change!

As for the two principal gamblers, after the collapse of Law’s System in 1720 “Beau Gage” went into hiding in the Parisian underworld before joining Mary Herbert in Spain as the prospector and manager of her mining operations in the south of the country, mainly at Guadalcanal, Cazalla, Galaroza, Aracena and Rio Tinto in the Sierra Morena. She obtained the lease to work these sites on the strength of her family’s successful lead-mining operations in Montgomeryshire, but all the profits made from these Welsh mines went towards paying off her debts. She was thereby left with insufficient capital to fund her Spanish projects. In these she used Gage as her factotum but in the meantime continued to elude his attempts to make her his wife. Nonetheless, Joseph proved too wily to be entirely defeated, as we know from his marriage in 1747 to the “well-dowered” Catherine Caryll. Catherine was the daughter of the Earl of Seaforth’s sister, Lady Mary Mackenzie, who just happened to be the main beneficiary of Kenneth Mackenzie’s (and hence Anne Carrington’s) estate. Catherine was, of course, also the granddaughter of Frances, Countess of Seaforth and the great niece of the other Herbert sisters.

The world of the Caryll family could not have been more different from that of Joseph Gage and Lady Mary Herbert. Caring quietly for his estates, which had once stretched from Shoreham to Guildford, John Caryll was celebrated by his devoted friend, Alexander Pope, as “the best man in England”, a model of Christian charity and responsible husbandry. The family was dismayed at the prospect of Catherine marrying Lady Mary Herbert’s notorious business partner and admirer – a man who had clearly for so long been entangled in litigation with Mary and her aunt. Indeed, the way in which the worldly Joseph Gage had lured the gentle and innocent “Kitty” Caryll into his web might have formed the plot of a melodramatic novel or play of the time.

Anne Carrington had transferred the bulk of her wealth into the hands of her clandestine husband, Kenneth; and from a letter which he wrote in 1723, we learn that Kenneth subsequently changed his will. He had originally intended to leave everything to Lady Carrington; however, because of her circumstances, he now left his estate and saltworks (“the Salterns”) at Portsea, not to his wife but to Anne’s niece, Lady Mary Caryll (Catherine’s mother) – lest everything be seized by her creditors (or in his words, now that would all be “liable to the Engagement into which she had been innocently and unwillingly drawn”). At the same time he ensured that his wife had a subsistence from him in his lifetime and from Lady Mary Caryll thereafter. This bequest was then challenged by Mary Herbert purportedly on behalf of her aunt Anne. Mary had also claimed that she had lent Kenneth £3,333 5s 8d in order to buy the Northumberland estate of Thornton, and so was entitled to repayment. Having already successfully fought off previous claims, the Carylls were now appalled at the prospect of Catherine, with her dowry of £4,500, falling into Joseph’s hands. Her aunts were equally horrified: “Kitty has not yet completed her folly”.

A little over three months after the marriage in Paris, the bride was dead. Lady Mary had power of attorney over the estate acting on behalf of Joseph Gage and more litigation followed as Catherine’s sister, Elizabeth Caryll sued Gage for £2,200, supposedly left to her in her sister’s will. She had assured her brother that she had done all in her power to dissuade “the poor little thing” from encompassing her ruin, and warned him to be on his guard against Mary Herbert and her projects. As for Gage, she remarked bitterly “I think he will get enough for two months’ living with our poor sister, in short, brother, he shews himself in his own colours.” “Count Gage”, for his part, made a particular point of cherishing what he portrayed as a pure love match. 15 years later he wrote to Elizabeth that not a day passed when he did not remember his dear wife, “which is now in heaven a-praying for us”.

In all of this drama it was a testament to Kenneth’s wily legal skills that he had managed to fight off Mackenzie Quin and Cantillon’s persistent attempts to claim the Herbert debts. By keeping their marriage a secret and cannily transferring the bulk of Lady Anne’s estates into his own name, he was able to keep her property safe from the constant onslaught of litigation from her creditors throughout the 1720s. By then extending this subterfuge by making his niece, Lady Mary Caryll, his main beneficiary he managed to keep their estates still urther out of reach of their enemies. In the event, we know these tactics to have proven ultimately successful: long after both his and Lady Anne’s deaths, as late as 1740 Lady Mary Caryll was still in possession of the valuable Salterns – and even by 1762 we find Joseph Gage’s dispute over the £3,333 5s 8d loan for the Thornton estate wholly unresolved.

By way of a final postscript to this story, we learn that George Mackenzie Quin was later to have a son, named Quin Mackenzie Quin, who it seems was something of an infant maths prodigy. At the age of eight he wrote a Method, for multiplying and dividing very large numbers of figures simultaneously, which his father published in 1750 and had him present to King George II. Curiously, it seems a copy of this obscure work later found its way into the library of Count Joseph Gage’s estranged brother, the 1st Viscount Gage, at Firle Place. (And it also did so into that of Lewis Carroll, where it may even have inspired sections of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland). In Voltaire’s Candide (published in 1759), Candide goes to Paraguay where he meets the King of El Dorado. This is an exact mirror of the Kingdom of Aacaniba which in 1755 Quin Mackenzie Quin – who had now reached the rather more mature age of 16 – translated and published in London. This supposedly factual voyage of exploration by Matthew Sagean was only four years before the publication of Candide and was about a journey up a river to the west of the Mississippi where the author allegedly encounters a kingdom of native Americans living in gilded splendour under a king descended from Montezuma. And the name of the manservant whom Candide acquires in this part of the narrative is named Cacambo. This seems to be a word closely related to Aacaniba. It appears that Quin’s interest in this subject matter was almost certainly inspired by his father: on 25th November 1725, after French settlers of Illinois sent Chief Agapit Chicagou of the Metchigamea and five other chiefs to Paris, they met with Louis XV and Chicagou had a letter read pledging allegiance to the Crown; they later danced three kinds of dances in the Theatre Italien, inspiring Rameau to compose his rondeau Les Sauvages. George would have been at the Court of Versailles at the very time of this visit. Furthermore, if you follow the Mississippi up as far as St Louis, the River Illinois is to the west; and, according to the Gentleman’s Magazine of 1755, the Regent Orléans had actually set up the Mississippi Company on the strength of the very book by Matthew Sagean which Quin Mackenzie Quin later translated.

Andrew and Kevin McKenzie wrote May we be Britons? – A History of the Mackenzies – and the two brothers are currently in the process of writing a further family history which touches upon some of the material in this article: Coatimundi – Intrigue, Piracy and Rebellion – the true story of an unlikely witness to some of the most turbulent years of Scotland’s history. You can purchase a copy of this book by clicking HERE