Firle During WW2

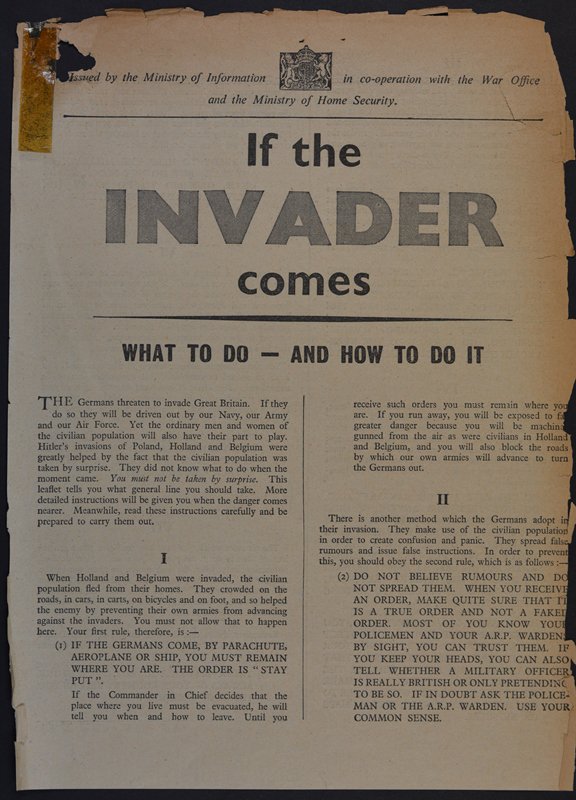

During World War Two, Firle was vulnerable to enemy action; the German forces were barely 70 miles across the English Channel on the coast of France. At the start of the war, Germany was expected to invade England; such an invasion would rapidly engulf Firle and the towns, villages and farms of the South Downs. Wanting to come to terms with Britain, in July 1940, Hitler made his ‘Last Appeal to Reason’, but was rebuffed. People were braced for invasion and pored anxiously over an official pamphlet ‘If the INVADER comes’. There was paranoia about spies and traitors. It was an extremely worrying time. The Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, exhorted the people to ‘STAND FIRM’ and told them what to do in his message to the nation ‘Beating the INVADER’

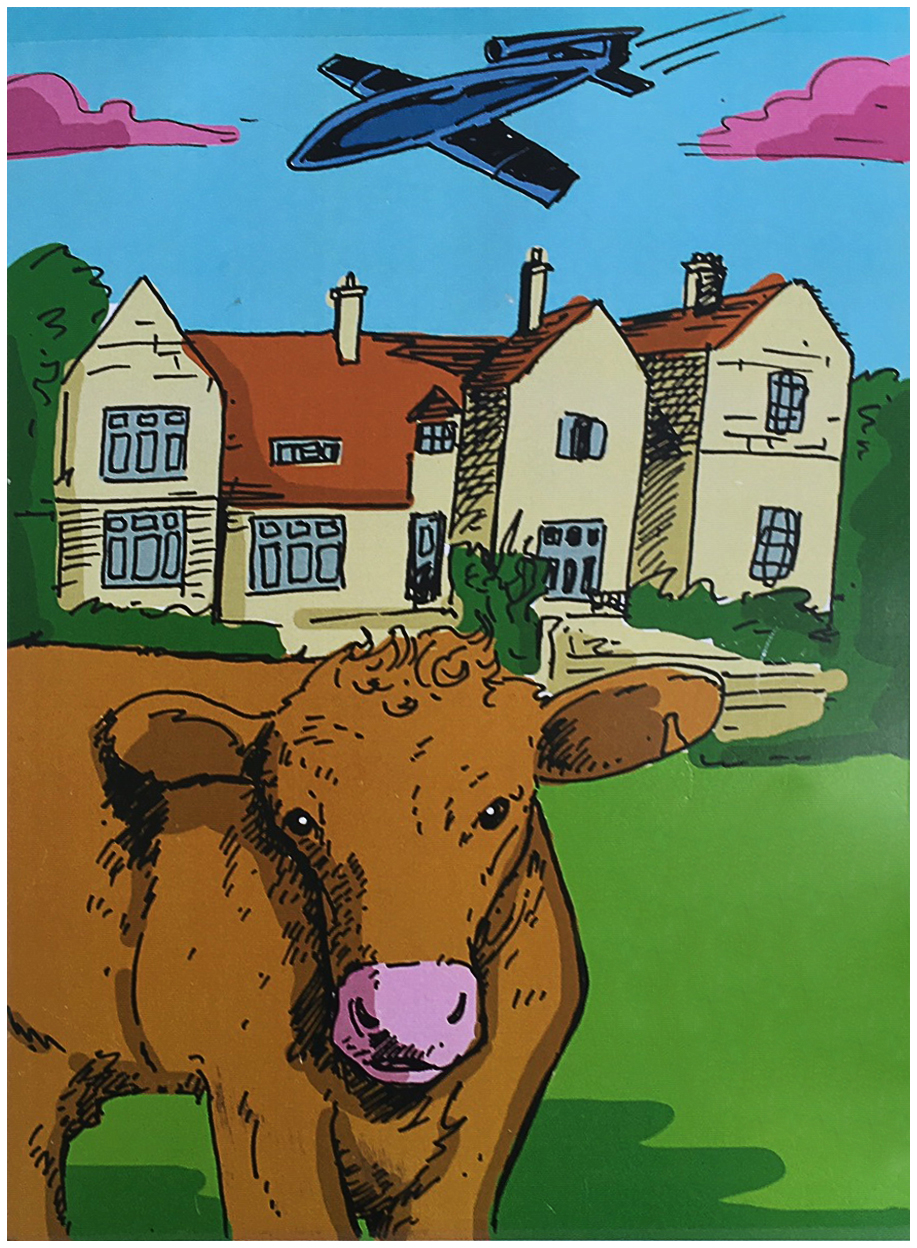

The invasion was postponed because of German plans to invade the Soviet Union and the success of the Battle of Britain. However, German planes randomly dropped bombs over Sussex, if they still had bombs in their holds after blitzing London; people and livestock were killed in Firle. There were also frequent accidents, such as when an allied Spitfire hurtled into Firle’s old workhouse, the Stamford Buildings, and destroyed it.

The tide turned as Germany got bogged down in the Soviet Union and America entered the war after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. The South of England changed from defensive to offensive posture. Firle, among other villages, became a huge gathering area for the invasion of occupied France. The downland above Firle had been cleared of gorse to increase farm productivity only to be converted into a firing range; the locals were regularly submitted to a terrible noise. Tony Monnington, one of those who farm the downland today, has found many shells in the soil; his farm, Black Cap, is riddled with small craters.

For the locals, life was no less worrisome than it had been earlier in the war. After the Normandy landings on D Day, 6 June 1944, Hitler launched his ‘vengeance weapon 1’ or the V1 flying bomb (‘doodlebug’). Intended to punish Londoners, they frequently veered off course and many came down before reaching London. In a two month period in 1944, no less than 814 fell in East Sussex.

Firle was luckier than the area round Bexhill and Hastings, which bore the brunt of the V1s. One that landed very near Firle blew out all the windows of Firle Place. It deafened the long-serving vicar, the Rev Andrew Gregor, who was sitting in a chalk pit, 100 yards below the point of impact; his bible was said to have been torn to shreds, but he survived the ordeal, retiring in 1946 after the war. The V1 had no capacity to find a target, but were weapons of terror rather than of targeted destruction, which blew up on landing.

The V1, and its successor, the V2 ballistic missile, continued to spread havoc in Southern England almost until victory was declared in Europe, on VE Day, 8 May 1945. Kate Lusted’s diary records the happy day: ‘Put out flags. Skinned rooks for pie. Went to Ram for a drink. Bonfire and torchlight procession.’ Meat was rationed; Firle’s abundant rook population was a valuable source of pie components, but preparing them was a lot of work. Many were needed for a decent helping and, apart from skinning them, the fleas had to be removed. Frances Partridge, in her diaries, records how Quentin Bell, of Charleston on the Firle Estate, celebrated by making a life-sized image of Hitler to burn on the top of Firle Beacon.

The Canadians

At the start of the war, Southover Manor School moved into Firle Place and the Gage family had to find somewhere else to live. However, by 1941, it was becoming apparent that Sussex would be the launch pad for the invasion of Europe; the school was displaced and the house taken over by Canadian forces; Firle was described by one resident as being ‘under siege’ by them. Men from the South Saskatchewan Regiment occupied Firle Place; others were under canvas in Firle Park. Preston House was occupied by Canadian troops. Firle Park became a key transit camp, from which locals were banned; thousands of Canadian and other allied troops passed through it in preparation for the Normandy landings.

The Canadians had arrived in Sussex in 1941; at first they were deployed in a static role, to defend the South of England. However, the Canadian General McNaughten requested that ‘the claims of the Canadian Forces to form the spearhead of any offensive would not be forgotten’. Tragically, the first such offensive came in the following year, when Canada supplied by far the largest contingent of troops in the disastrous Dieppe Raid; some 55% of the 6,000 troops involved were killed, wounded or captured. The disaster was keenly felt in Firle and in East Sussex generally, as many of them had been stationed there.

There were altercations between residents and Canadians, often fuelled by alcohol, which was more freely available than at home in Canada. Rainald, 6th Viscount Gage, recalled Canadian soldiers who ‘…broke into the cellar and drank all my wine. I remember I had several dozen excellent vintage White Burgundy, which I was told they drank laced with gin.’ Lord Gage’s daughter, Camilla, remembers a drunken Canadian mistaking her pet donkey, Peggy, for a ghost, after it had wandered into the churchyard. At their departure, the Canadians left Firle Place, in a terrible condition; it was several years after the war before the Gage family could resume residence.

After D Day in June 1944, Firle and its neighbouring villages gradually came back to normal. Despite the upheaval created by the Canadians, many Firle residents formed warm friendships with them. Kate Lusted and others set up a canteen in the village hall for them and, after the war, cordial correspondence was maintained for some years. The Canadians’ courage and sacrifice was universally recognised. Whatever inconvenience might have been caused by them, all was forgiven for the gallant Canadians, who had played such a major part if winning the war.

The Home Guard

In May 1940, soon after Winston Churchill became Prime Minister, volunteers, aged between 17 and 65, were invited to join what came to be known as the Home Guard. Its function was to defend the localities where they lived. They were unpaid part-timers, who wore military uniforms and were armed. The policy was hugely popular and, within three months, 1.5 million had enrolled.

Firle came under the wing of the 16th Sussex Battalion, based at Lewes. By the end of June, its enrolment had reached 2,200; they came from every walk of life, from a cowman to the chairman of Barclays Bank. Firle contributed 58 volunteers to the Lewes Battalion. The Firle platoon was commanded by Dennis Bush, agent of the Firle Estate and Mr Gribble a farmer on the Firle Estate. Some Firle Home Guard members are shown in the group, such as Tom Lusted (back row, with glasses) and John Hecks.

The Home Guard has been the subject of much satire over the years, notably through the TV series Dad’s Army, and it is true that its activities could appear comic or chaotic. Once an order was made to arrest all nuns, on the basis that they might be German troops in disguise; in fact, the Germans had used this ruse in France. There was an inevitable shortage of weapons, as the regular forces had to have priority; their ability to improvise weapons, such as pitchforks, pikes, spades and clubs provoked derision. Yet their role in defending the nation’s infrastructure and providing early information on damage to it was vital, as were many of its other activities. Had there been a German invasion, their role in delaying the German advance and providing intelligence would have been invaluable. Any of them captured by the Germans were likely to be shot and they knew it.

John Hecks, a local farmer, was a fairly typical Home Guard member. He did night duty twice a week, guarding the Lewes to Newhaven road and patrolling the railway track with an automatic rifle. A common Home Guard job was surveying the countryside for suspicious activities from a high vantage point, such as Mount Caburn or Firle Tower – where John’s fellow watchman, Horace Phillips, introduced him to the joys of drinking whiskey. Cables were placed across the Downs to stop German gliders from landing. Another task of John’s was disposing of dead cattle, often the victims of stray German bombs.

Particularly brave were the Auxiliary Units; they were small groups trained in telecommunications, sabotage, intelligence gathering and survival. They were to remain behind the lines overrun by the German forces in the event of an invasion. If they were captured by the Germans, they could expect no mercy. Among Auxiliary Unit members were William Owen, steward of the Firle Estate, and Bill Webber, a Firle market gardener.

The Auxiliaries were sworn to secrecy about their work and it could lead to difficulties. When John Hecks’s uncle, Eric Brickell, a local farmer, resigned from the ordinary Home Guard to undertake a role with the Auxiliaries, his family somehow knew not to ask any questions, but outsiders commented on what looked like unpatriotic behaviour in abandoning his Home Guard uniform. He was in a most unenviable position.

Relations between the regular forces and the Home Guard could be tricky. When Lieutenant General Bernard Montgomery (‘Monty’) was appointed GOC South-Eastern Command in November 1941, he made a point of trying to foster ‘the feeling of mutual respect and comradeship’ between them. The largest contingent of troops was Canadian and their Army History refers to ‘intimate and friendly contacts with the Sussex Home Guard’. General Crerar praised the ‘kindness, sympathy and understanding of the Sussex people’ towards his Canadian troops. The Home Guard’s touching gesture in giving £676 to the Canadians recognised the help given by them.

By December 1944, there was no risk of a German invasion and the Home Guard was stood down. The Eastbourne Town Council passed in a resolution expressing its gratitude for the fortitude and cheerfulness of the Home Guard members ‘…without regard for their personal comfort and safety, maintaining ever the sense of duty, courage and tenacity which accord with the best traditions of our people and, on behalf of the townspeople of Eastbourne, do desire to convey to all ranks this expression of heartfelt thanks’. These sentiments could apply to Firle’s Home Guard platoon and 25,000 similar ones up and down the country.

Firle residents’ reminiscences

Despite German attacks from the air, the prevailing anxiety, the regulations and rationing, life carried on mostly as normal. Firle’s shop and post office remained open, as did Beales the butcher. There was a table tennis club in the village hall. Car usage was very restricted, but trains ran normally; George Hayton Baker commuted daily to the London Stock Exchange, leaving his son Lyn to manage Hall Court Farm, which was acquired by the Hecks family after the war.

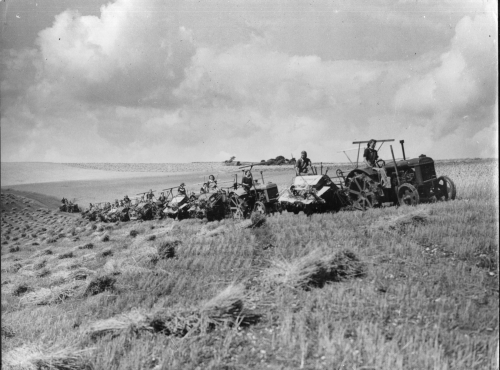

Reginald Hecks had come from the West Country to New House Farm, Firle in 1912, to be closer to the London market for sales of milk. Throughout the Second World War, he and his son, John, farmed there. Reginald was held in high esteem by the authorities and was a member of the local War Agricultural Executive Committee; known as WAR AGs, they were intended to help farmers increase their production and they were graded accordingly.

John combined working on the farm with his Home Guard duties; there were normally about four men working on the farm as well as four land girls. Sometimes, German prisoners were brought in to do the very heavy work. Among those who worked on the farm were two conscientious objectors, David Garnett and Duncan Grant, members of the Bloomsbury Set, who lived at Charleston; Grant joined the Home Guard and squared his conscience by having an obsolete rifle for which no bullets were available. One of John’s men, George Hughes, participated in the allied invasion of Germany in 1945 and brought back a German bride…which was considered rather scary; emotions ran high in those days.

Land Girls on Firle Beacon

John Hecks at one time provided ponies for Lord Gage’s children, Sammy, Nicky and Camilla. John’s sister, Betty, ran a home school for them. Later, the Gages moved away from Firle. They were billeted on the Cadwallader family in Welshpool and later lived at Eton, whence Lord Gage commuted daily to London for his secret work in SOE, which involved spreading ‘fake news’ to disconcert the enemy. They thus avoided the doodlebug which deafened the vicar and tore his bible to shreds. Evacuation, particularly of children, was an official policy; the Lewes area, at the war’s start, received no less than 16,000 (of which 53 went to Firle).

Families had to endure the separation of parents and children, who were often billeted with grandparents or friends in safer parts of the country. Complete strangers generously took in evacuees, such as the Cadwalladers for the Gage children. John B Gage, a kinsman, mayor of Kansas City offered to host them in America for the duration of the war. The offer was not taken up; the Brickell farming family received a similar offer from Canada, which was also not accepted. Families preferred to stick together, come what may; those that stayed felt a bit superior to those that crossed the Atlantic for greater safety – which was by no means assured, given the risk of being sunk by a German submarine on the voyage.

People were ever on the move as the fortunes of war changed. While children were being evacuated, Firle residents were taking in lodgers. The Brickells welcomed Canadian Cameron Highlanders, who would help on the farm. Mrs Brickell was particularly fond of one, Bill French, and cheerfully said ‘see you soon’ as he left for the front, to which he replied ‘I shall never see you again’…within a few weeks, he was dead. None of the local farms or houses received a direct V1 hit, but the risk was constantly in mind, as was the risk of being poisoned by enemy gas.

The Lusteds, who lived at Scaynes in the village, used to host London firemen, who came to Firle to recover from the horrors of firefighting in London’s blitz; their presence enabled the Lusteds to have the luxury of a telephone (Jim Lusted still remembers the number, Glynde 217), so that the firefighters could be summoned at short notice to resume their dangerous work in London. It was a time when everyone cooperated and improvised for the common benefit. David, the son of farmer William Rowsell, used his experience of farm machines to repair army vehicles. Even schoolchildren helped on the farm; Richard Brickell’s diary is full of references to sorting sheep, loading straw or mixing ‘cow’s grub’, after doing his home work.

There was no television; people relied on newspapers and the BBC’s ‘wireless broadcasts’. Cinemas flourished; there were two in Lewes. In Firle, the Riding School was converted into a make-shift cinema. Lord Gage’s daughter, Camilla, recalls enjoying Popeye the Sailor cartoon films; her mother, Imogen, served tea to those present. The Ministry of Information sponsored films, which combined excellent entertainment with subtle propaganda. As a schoolboy, Richard Brickell greatly enjoyed such masterpieces as The Young Mr Pitt and The 49th Parallel – the latter intended to sway US public opinion towards Britain.

We wish to acknowledge with many thanks the pictures of the Land Girls supplied by Records of the East Sussex War Agricultural Executive Committee and the East Sussex Agricultural Executive Committee held at The Keep.